Saving Mississippi’s “freedom houses”

As voters head to the polls, a movement is underway to preserve safe spaces once used by activists helping register African Americans

Mississippi has an uneven record when it comes to preserving historic architecture, which has led to the loss of extensive evidence of its complex, entwined historical narratives, including structures associated with efforts to register African American voters.

Historic preservation efforts have frequently focused on antebellum slaveowners’ lavish homes, while related slave dwellings are allowed to fall by the wayside. Also neglected has been the built evidence of the civil rights era, which a new initiative by the nonprofit Mississippi Heritage Trust aims to address. During the era, registering African Americans to vote was front and center, and what were known as freedom houses played a pivotal role in helping overcome widespread suppression.

The Mississippi Freedom House Project focuses on the modest structures that provided comparatively safe refuge for voting rights activists during the tumultuous era. The trust placed Mississippi’s freedom houses on its 2019 list of the state’s 10 Most Endangered Historic Places and in the years since has added the Unita Blackwell house and shotgun cabin in Mayersville and the Knoxo freedom schools and the Alyene Quin house in McComb.

As the trust notes on its website, “The houses where civil rights workers stayed and leaders of the movement convened to strategize about voter registration drives such as Freedom Summer of 1964 are often in poor condition today and will soon be lost if immediate action to stabilize them is not taken.”

Meanwhile, the people capable of detailing stories associated with such structures are passing from the scene.

Unita Blackwell, a voting rights activist and later the first Black mayor of Mayersville, in Issaquena County, died in 2019, but when I visited her Mayersville home in the 1980s she recounted an episode that illustrates the intersection of oral histories and the built environment.

Blackwell recalled that when actress Shirley MacLaine came to Mississippi to support and document the civil rights movement, she spent a night in Blackwell’s shotgun house. MacLaine had little experience with such dwellings, and at one point asked to use Blackwell’s bathroom. Blackwell said she pointed to a door at the rear of the house, and a few moments later, MacLaine returned, confused, and said she had gone through the door in search of the bathroom but that it had led outside. Blackwell laughed and informed her that the bathroom was an outhouse.

Blackwell said she was unaware of MacLaine’s movie star status at the time and was befuddled when she asked where she could plug in a tape recorder, because her house had no electric outlets. Blackwell’s shotgun house is still there, but it is abandoned and the outhouse is gone. The nearby home that Blackwell later occupied has been reroofed using a Mellon Foundation Monuments Project grant.

In 2021, the National Park Service’s African American Civil Rights Grant Program awarded the Mississippi Heritage Trust $50,000 to identify and document Mississippi’s surviving freedom houses. The Mellon monuments program later awarded the trust $576,000 for its freedom house project, which is being used to host workshops and educational sessions for freedom house owners; to stabilize the Unita Blackwell house and cabin in Mayersville and the C.C. and Emogene Bryant house in McComb; and to produce a documentary film on efforts to save and repurpose the structures.

Partnering with the trust are the Alluvial Collective; Blue Magnolia Films; the Mississippi Alliance for Nonprofits and Philanthropy; Rise Roofing and Construction; and The Tell Agency.

Other properties included in the project are the Cleveland, Mississippi home of Amzie Moore; the Canton Freedom House; and the Indianola Freedom House.

NAACP field organizer Bob Moses frequently stayed in the Bryants’ McComb house when he was organizing in Mississippi, as did Medgar Evers and other less known yet consequential activists working with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and the Council of Federation Organizations (COFO). Moore’s home, which has been restored, likewise provided sanctuary for key figures in the civil rights movement including Evers, Martin Luther King Jr., Fannie Lou Hamer and SNCC organizers during Freedom Summer in 1964.

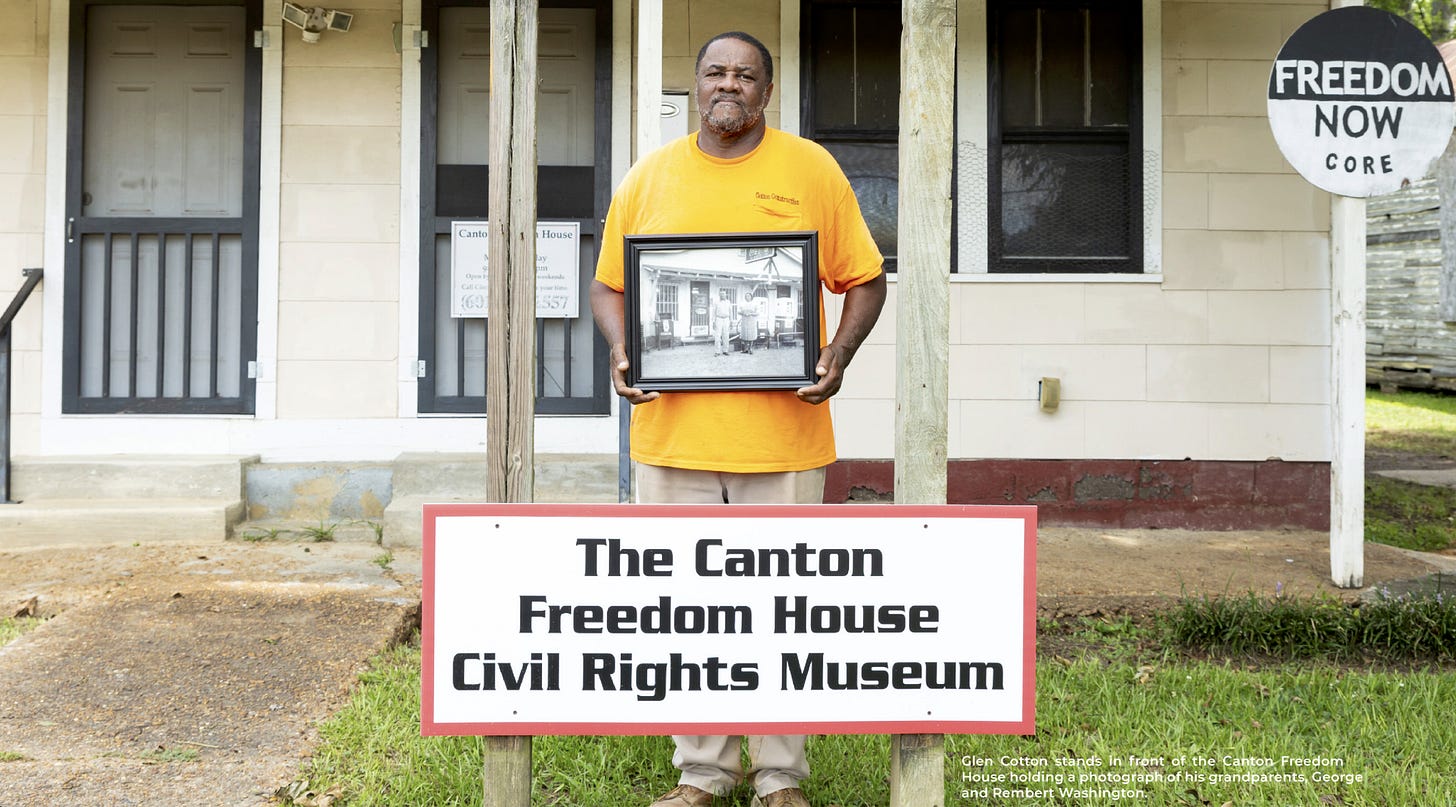

Freedom houses in Canton and Indianola served similar roles. In Canton, a store and adjacent rental homes owned by brothers George and Rembert Washington provided lodging for organizers including King Jr., James Meredith and workers with the NAACP, SNCC and the Congress of Racial Equality, as well as a meeting place, community hub and clearinghouse for printed flyers that were circulated through the community. Most of the original structures are gone, but one rental house has since been restored as the Canton Freedom House Civil Rights Museum; among its artifacts is a map showing places of refuge for activists while in the field. The windows of the house are covered with chicken wire, as was common during the era to deflect Molotov cocktails that were sometimes lobbed inside freedom houses by white terrorists.

The Indianola freedom house, originally owned by Estell King, was the second in the community, used after the first was bombed. A descendant has been laboring for years to stabilize the property in hopes that a full restoration will eventually be possible.

Image: Descendant Glen Cotton stands before the Canton Freedom House; photo by Abby Seale, via Mississippi Heritage Trust website