When contraception became a conservative target -- the first time around

A century ago, women’s rights advocates were jailed for distributing information about birth control under the 1873 Comstock Act, which prohibited using the U.S. mail to distribute almost anything related to sexuality or human reproduction.

In 1916, Margaret Sanger, a nurse and women’s rights advocate who opened the nation’s first family planning clinic in New York City, and popularized the term “birth control,” was jailed for mailing such periodicals, during which she went on a hunger strike and was force-fed. In an earlier episode, she had fled the country to avoid being imprisoned. Her sister, nurse Ethel Byrne, and husband William Sanger were arrested for similar offenses.

Sanger’s trial judge succinctly articulated the prevailing view among conservative American males, ruling that women did not have "the right to copulate with a feeling of security that there will be no resulting conception.”

After Sanger appealed her conviction, another judge ruled that doctors, at least, could prescribe contraception, which was an incremental yet significant advance.

The United States in the 1910s was beset by a level of political divisiveness equal to – and, at times, exceeding – what it is experiencing today. Birth control was considered a radical concept, with conservatives vehemently opposing its use, much less its legalization. From a contemporary perspective, that may seem like a puritanical throwback, yet vice presidential candidate J.D. Vance has proposed resurrecting the Comstock Act, this time to restrict mail-order abortion pills, as the Washington Post reported. (Note that some links cited in this report are paywalled.)

Numerous elected officials and conservative groups have suggested revisiting the right to birth control itself, and some state legislatures have introduced bills to restrict access or that allow healthcare providers to refuse to provide it. Running counter to this trend, the Federal Drug Administration in 2023 approved a nonprescription, over-the-counter daily oral birth control pill (Opill), which expanded public access.

Disparate forms of birth control have been practiced throughout human history, and likely during prehistoric eras (see “The History of Birth Control: How We’ve Been Trying to Prevent Babies Since the Beginning of Time”), but it became more pervasive with the development of more reliable mechanisms, which today includes prescription drugs – i.e. “the pill,” as well as more trustworthy condoms and intrauterine devices. Advances in contraception facilitated greater sexual freedom starting in the 1910s, during what was known as the Progressive Era, when outspoken liberals sought to upend social and economic norms. Movements related to women’s suffrage, labor unions, socialism, anarchy, and the scandalous concept of free love inevitably sparked a conservative backlash, including against contraception. The general public was less sanguine, in part because soldiers had experienced firsthand the efficacy of birth control after the military provided them with condoms during World War I. The military also provided soldiers with birth control information that Sanger had published, though without attribution because her periodicals had been banned by the government.

The 1910s were a time of mass cultural change and widespread public violence, including corporate massacres of striking workers and frequent terror bombings, as well as the nation’s first antiwar protests, the rise of labor unions, the spread of government and private surveillance, and conservative efforts to curtail an array of citizens’ rights. The fight over birth control was part of the mix.

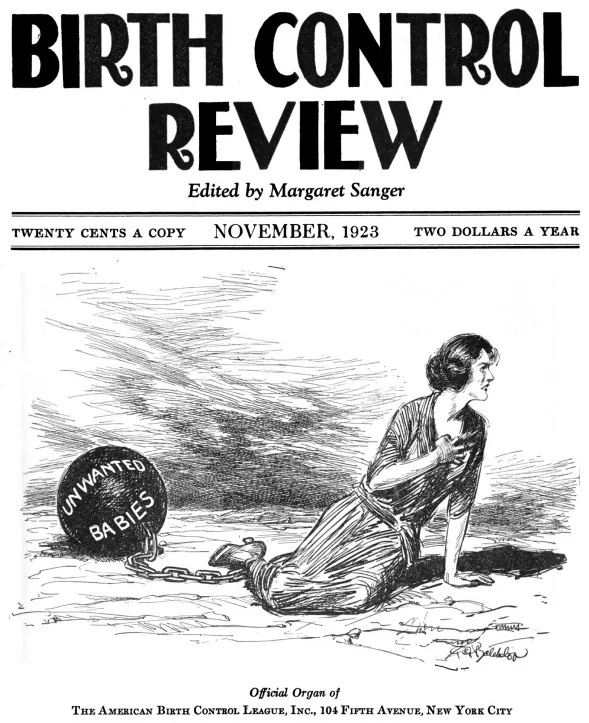

Sanger, who saw contraception as a means of empowering women and to reduce the need for terminating dangerous or unwanted pregnancies, argued in a 1918 issue of her periodical Birth Control Review that for women it was “the first step she must take to be man’s equal. It is the first step they must both take toward human emancipation.”

Sanger’s family planning organization eventually evolved into Planned Parenthood, though the group has since disavowed her due to her association with eugenics beliefs. She also opposed abortion in most cases and refused to facilitate such procedures as a nurse.

The era’s opposing argument over contraception was summed up by Catholic author G.K. Chesterton, whose musings in the U.K. were embraced by conservatives in the United States. Chesterton considered the practice self-indulgent, immoral and unnatural. “Birth Control,” he wrote “is a name given to a succession of different expedients by which it is possible to filch the pleasure belonging to a natural process while violently and unnaturally thwarting the process itself.”

Anarchist lecturer and advocate Emma Goldman, who spent most of her life trying to undermine government and corporate control of Americans’ lives (sometimes through violence), was imprisoned multiple times and in 1919 was deported to her native Russia. In her autobiography, she wrote that as a midwife she had observed the misery of overworked women bearing multiple undernourished children in New York City’s squalid tenements, while wealthier women had access to underground birth control.

Goldman initially avoided discussing specific birth control methods in her lectures because she was disinclined to go to jail for it, but later engaged in what she described as the “first public discussion” of such details. Because she was not immediately arrested, she began to lecture more freely on the topic. Her eventual arrest, in 1916, arguably backfired, in that it sparked nationwide protests and wider interest in birth control.

As late as 1926, U.S. Sen. James Reed of Missouri argued, “Birth Control is chipping away the very foundation of our civilization.” Yet by then, support for contraception was growing and becoming increasingly nonpartisan. As The New Yorker’s Jill Lepore reported, a 1927 survey of nearly a thousand members of Sanger’s American Birth Control League found that its membership was more Republican than the rest of the country’s citizenry. During the Depression that followed, when more people were interested in having fewer children, Gallup polls found that three out of four Americans supported the legalization of contraception. Then, in 1931, a federal appeals court removed contraception from the category of obscenity.

Still, the right to birth control was not yet the law of the land.

Sanger continued to press the case in court, and in one of her legal victories, a court ruled that medically prescribing contraception to save a person's life or well-being was not illegal under the Comstock Act. The ruling prompted the American Medical Association in 1937 to define contraception as a normal medical service and a key component of medical school curriculums. By 1938, hundreds of birth control clinics were running in the U.S. despite the fact that their advertisement was still illegal.

By the 1950s, birth control was gaining acceptance as a means of population control. Then came the sexual revolution of the 1960s, which was partly facilitated by access to the pill. In 1965, after the executive director of Planned Parenthood of Connecticut was arrested for opening a birth-control clinic, the Supreme Court declared in Griswold v. Connecticut that the state’s ban on the use of contraceptives was unconstitutional, rendering restrictions on birth control in the Comstock Act effectively null and void. The right was later extended from married couples to single people.

In 1969, President Richard Nixon pushed Congress to increase federal funding for family planning, and the following year he signed into law Title X, a federal grant program providing family planning services, which was credited with reducing the number of abortions nationwide.

Then came another backlash. In the 1980s and 1990s, the Republican party began reconsidering its support for birth control, which some felt ran counter to its “family values” agenda, the Washington Post reported. Title X is today a frequent conservative target.

Though a minority of private citizens express opposition to some form of birth control, some cite religious objections, and the nation’s culture wars have resurrected old divisions, with birth control sometimes associated with abortion and promiscuity. As a result, the political backlash has continued to gain steam.

In 2014, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of craft store chain Hobby Lobby that employers with religious objections can refuse to cover contraception. Meanwhile, Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas said that it may be time to revisit Griswold v. Connecticut.

As a result, access to birth control is once again subject to debate.

Next up: How Mississippi came to the forefront of debate about the future of contraception

Image: Mailbox graffiti, via Wikicommons; cover of November 1923 issue of Birth Control Review, via Wikicommons

Alan Huffman is a freelance writer, author and political researcher based in Bolton, Mississippi. His work has appeared in The Atlantic, The Guardian, the Los Angeles Times, the New York Times, ProPublica, the Washington Post and numerous other publications.

Maybe the question isn’t “can we?” But “should we?”