Prison book club launches unique podcast

Inside a maximum-security prison in rural Mississippi, a space for listening, reflection and redemption—and for the rest of us, an opportunity to listen in

When Micharlos joined the inmate book club at the Wilkinson County Correctional Facility, he did not intend to talk about himself. Like other club members, he joined to open his eyes to different worlds, and to briefly step outside the confines of incarceration.

But after immersing himself in books about a range of topics, from slavery to war and the story of two brothers fractured by a family’s broken love, he began to see echoes of his own life in the struggles of the characters. The act of reading and discussing these books drew him back to the moment that altered his and many others’ lives forever, an incident he wishes he could undo.

In the new documentary podcast “Hidden Mirrors,” Micharlos reflects on his response to his brother’s murder while discussing the choices made by characters in literature. Confronted with his own family’s loss, he weighed different paths and ultimately embraced the darkest one. Among the potential responses he considered, he says, “The first thing is revenge. And I went and got exactly that.”

As listeners, we do not learn precisely how that revenge unfolded, only that it led to Micharlos’ imprisonment. What we do hear are raw, unfiltered reflections from inside a prison, captured live and in the moment. That rarity is part of what makes “Hidden Mirrors” so striking.

Launched on Oct. 15, 2025, “Hidden Mirrors” follows the conversations of the book club at the prison outside Woodville, Mississippi, led by journalist and author Alan Huffman (editor of The Mississippi Independent). Huffman began volunteering with the group through a statewide humanities program that sponsors 16 prison book clubs. After months of guiding discussions inside a windowless cinderblock classroom deep within the prison, he realized the exchanges were far more than casual talk about literature.

“I didn’t really know what to expect, starting out,” Huffman said. “But I’m always up for talking about books. I figured these guys would have fresh perspectives, and that I might also learn from them. I had no idea how profoundly illuminating their discussions would be, on so many levels.” He noted the irony of discovering common ground with men whose lives seemed so different, especially given the divisions that often stifle meaningful dialogue today, outside the prison walls.

“We all have different life experiences, for better or worse, but one of my guiding lights is that everyone knows something I don’t, and it pays to listen,” Huffman said. “Books turned out to be a very good vehicle for doing that.”

Micharlos’s openness is typical within this rarefied circle, officially known as the Inspired Readers club. Listeners to the first five episodes hear how the rigid hierarchies and constant vigilance of prison life are set aside, replaced by moments of vulnerability and reflection. In their place emerges a different kind of order, one built on listening, patience and a gentler respect than what’s demanded back in the cellblocks. That atmosphere has ripple effects: Huffman notes a waiting list of about 50 inmates wanting to join the club, which currently includes 25 members with widely varied reading skills and personal histories.

What unites the men is a shared fascination with books, as entertainment, as conversation starters and as sources of human truth. The selections, chosen from lists Huffman proposes and the members vote on, surface characters and moral dilemmas that reveal dimensions of humanity rarely visible or discussed inside prison walls. The group conversations unfold in a complex setting: a facility with a strong education program but also a history of violence.

“The book is a mirror,” Micharlos observes, in explaining his desire to be heard by the outside world, which inspired the creation of the podcast and its name. “We see the reflection of ourselves in every book we read. We just have to read it and see how that gravitates towards us.” Before the podcast, he notes, those reflections—and the perspectives behind them—remained hidden.

Getting beyond violence

Wilkinson is a privately run prison with a documented history of violence—assaults, gang activity, suicides, murders. The federal government sued Mississippi over those conditions, noting that some men spend 23 hours a day locked in their cells. Many will never leave. Huffman initially assumed leading a book club there would be straightforward: He would propose titles, let the group vote, guide the discussions, then return to the outside world. Instead, he encountered a group of readers determined to use books as raw material to examine their own lives, and each other’s, in hopes of change. “They’re basically on a group search for truth, in books,” Huffman observed.

At one point, Huffman said, he wished that outsiders could hear what the men were saying, which sparked the idea for the podcast. Prison officials backed the idea and provided recordings of the sessions, supplemented by Huffman’s own deliberately unpolished recordings.

“I wanted listeners to be a fly on the wall,” Huffman explained. “I didn’t want this to be a heavily curated production with a performative feel. The point was to share these raw, provocative, thoughtful insights in context.”

Sebastian Junger, a journalist, filmmaker, and bestselling author of The Perfect Storm, Tribe, Freedom and War (the latter read by the club), told The Mississippi Independent that the podcast reveals men grappling with their histories through literature in unexpected ways. “Alan provided probably one of the only ways they could feel that,” Junger said. “It’s revealing of Alan’s determination, charm and dedication that he can go to what many would see as one of the worst places on earth, a prison in the Deep South filled with lifers who committed real violence, and nurture these beautiful souls who want to talk honestly about life.”

From its first episode, “Hidden Mirrors” wrestles with a central question: What happens when men in a hostile environment practice the avoidance of hostility, while searching for clues to life in books? A member known as Hopper tells us he joined initially to learn how to disagree without resorting to aggression, but that he soon found himself drawn deeply into the reading itself. Some members are longtime readers; others are opening books for the first time.

Huffman confesses on air that when he started, he thought the main point of the club would be reading, for obvious reasons—it’s a book club. “The idea that it also is teaching all of us to listen is something I did not foresee,” he tells the group in episode 4. What strikes him most, he adds in voiceover, is that “the guys listen very closely to each other, and respond honestly and directly.”

The first two books they discuss tackle very different wars. They begin with Ishmael Beah’s A Long Way Gone, a memoir of being forced into combat as a child soldier during Sierra Leone’s civil war. Later, they turn to Junger’s War, a visceral account of a U.S. platoon’s 15-month deployment to Afghanistan’s Korengal Valley. Beah’s story, of losing his family, being conscripted, and killing countless people while high on drugs, is harrowing. Yet inside Wilkinson, the men focus on his redemption and the broader theme of surviving trauma.

“What we all pretty much get from it is, like, hope,” says Deonte, one of the younger members. “All the things that Ishmael went through back then. And now, like, he’s a better man now, like a better person.” Justin, another member, argues that hope requires acceptance. Men who cannot face what they’ve done or where they are, he observes, risk severe mental breakdowns. Some take their own lives. That, he says, is the cost of denial.

Beah’s story resonates because it illustrates that redemption is possible. If someone can endure such violence, death and loss, and still rebuild, Justin believes, so can the men inside the prison. “Any man in here,” he says, “will be able to step out there into the world and make their own success story.”

Listening to reflections like these, it’s hard not to root for the readers. “You can’t help hoping that these men have the opportunity to have a better life someday,” Owen Phillips, a physician in Memphis who lives in Oxford, Mississippi, told The Mississippi Independent. “And I hope that being a part of this book club may have cracked open a door.”

The unsettling truth

At a time when portrayals of incarceration, on screen, in print and in the public imagination, often reduce people to their crimes, “Hidden Mirrors” offers a rare chance for listeners to see that these men are more than the mistakes that led to their convictions. “I think people in this country want to see inmates as just bad men, right?” Junger observed. “They’re evil, they’re bad. But really good, thoughtful people wind up in bad circumstances that encourage them to make bad decisions. The truth is much more unsettling. They’re just like us, like everybody else.”

Book club member Tyler echoes that sentiment, reflecting on Ishmael Beah’s ability to walk the streets of New York City after being rescued by the United Nations, his trauma invisible to passersby. “We really have no idea what affects a human being until we hear their story told,” Tyler says in episode 2. “I think it’s important for us to develop compassion and an awareness of the traumatic experiences of people.”

Micharlos adds that prison is not solely a place of misery and menace. “Some people want to see the good in you,” he says. “They want to see you be a better person.” This sort of observation is not what listeners might expect from a maximum-security inmate, but the idea is contagious and its influence extends beyond prison walls.

“As soon as the men began to speak, I realized there was something special going on,” Phillips recalled. “The men themselves were able to analyze character and themes in the books with deep insight. The respect that they had for each other’s opinions, and for Alan in his process, was apparent. I listened and relistened. When one man commented about having read The Great Gatsby in a different setting and another man says, ‘that’s a good book,’ you think what is happening here is truly special.”

Central conflicts

One of the most powerful episodes of “Hidden Mirrors” brings the Wilkinson book club into dialogue with Patrol Base Abbate, a national veterans’ reading group. Together, they discuss War, joined by Junger and Brendan O’Byrne, a former U.S. Army soldier and central figure in the book whose face appears on its cover.

The episode resonates because of the odd parallels between the two groups. Though their circumstances differ profoundly, both have endured extreme violence, death and the lingering trauma that follows. “There was a familiarity there, even though we were all strangers,” said Michael Jerome Plunkett, a U.S. Marine Corps veteran, author and facilitator of Patrol Base Abbate. “I was really impressed with these guys. They wanted to know so much about us outside of the book and our experiences of the military. They were so humble.”

For the men at Wilkinson, the similarities were unmistakable. “It’s just like war,” said a member known as Battle, after hearing O’Byrne describe deadly ambushes in the Korengal Valley. Another added, “It’s just like in the book—the fear of somebody making a decision with your life that could ultimately cause you to lose your life.” Listening to O’Byrne recount the dangers of Outpost Restrepo, Micharlos drew his own comparison: “This is an outpost to me.”

Junger, whose work often explores the intricacies of human behavior, outlined the connections he saw between the two groups. “They’re in a very hostile environment,” he said. “And being good at violence is a kind of solution, but it costs you morally, it costs you psychologically. I think they probably saw that similarity in one another—the kinship of having suffered and inflicted suffering, and in facing really hard circumstances. There’s something about that.” He added, “I think that probably felt good for them.”

Books sometimes hit close to home

For the club members, reading is often a paradox: an escape from prison life that also compels them to confront themselves and their violent pasts. In episode 5, Jesmyn Ward’s Where the Line Bleeds sparks a discussion about the complicated emotions surrounding Christmas, for both the novel’s characters and the incarcerated readers. For some, the story feels uncomfortably close to home. Ward’s novel follows twin brothers on the Mississippi Gulf Coast, abandoned by their mother to be raised by a blind grandmother while their drug-addicted father drifts in and out of their lives, tormenting one son and fueling his descent into instability.

”My mother left me when I was three weeks old,” says Justin, who speaks openly about his own fractured family. “I took the initiative to go out on a limb and go find my mother. We haven’t had a sit-down at a table and ate no dinner together and nothing before. Ever, still to this day. Only thing me and my mother has ever done is drugs together.” For Justin, the parallels were too painful. “That’s the reason I honestly stopped reading the book—because it was hitting home for me way too hard.”

Others in the group debate the absent mother, Cille. Some call her selfish for leaving her sons in her mother’s care. Battle acknowledges that she provided for them but insists she was never truly present. “She probably didn’t know what favorite color they like, what their favorite food was, or none of that, because she didn’t spend no time with them,” he says.

As Huffman notes, reflections on parenting aren’t likely what listeners expect from an inmate book club. Yet members often draw on their own fractured family histories to interpret the texts. Deonte compares Cille to his father, who drifted in and out of his childhood. As a boy, he longed for his father’s presence. As an adult, he sees things differently. “I understand him more,” Deonte says. “He a man. He was just trying to pretty much get his life on track. I got a son now. I don’t want my son feeling like I’m abandoning him because I’m in prison. I don’t want him to think I’m a selfish father, or I’m trying to abandon him. I’m trying to get myself together so I can make sure he don’t do the same thing that I did.”

As with the discussions of Beah’s book, this is a decidedly different take than many readers on the outside are likely to have.

Ward’s novel underscores a theme that runs through nearly every conversation in “Hidden Mirrors”: choice. Choices made by parents that shaped childhoods. Choices that carried men to war or prison. Choices that influenced their crimes, their capacity to return to society, and even the decision to show up for these literary discussions.

Micharlos circles back to his own choices in episode 1, not to excuse them or escape their consequences, but to name the moment when everything changed. “Hidden Mirrors” captures the rare process of incarcerated men learning, book by book, conversation by conversation, how to live with the aftermath of the decisions they’ve made.

“You still make your own decisions,” Micharlos reflects. “No matter what trauma we go through in life, you got a choice, just like me coming to prison. I do not want to be here and I see it every day, but I made a choice.” His choice now, he says, is to move beyond that, including by searching books for clues for how to go about it.

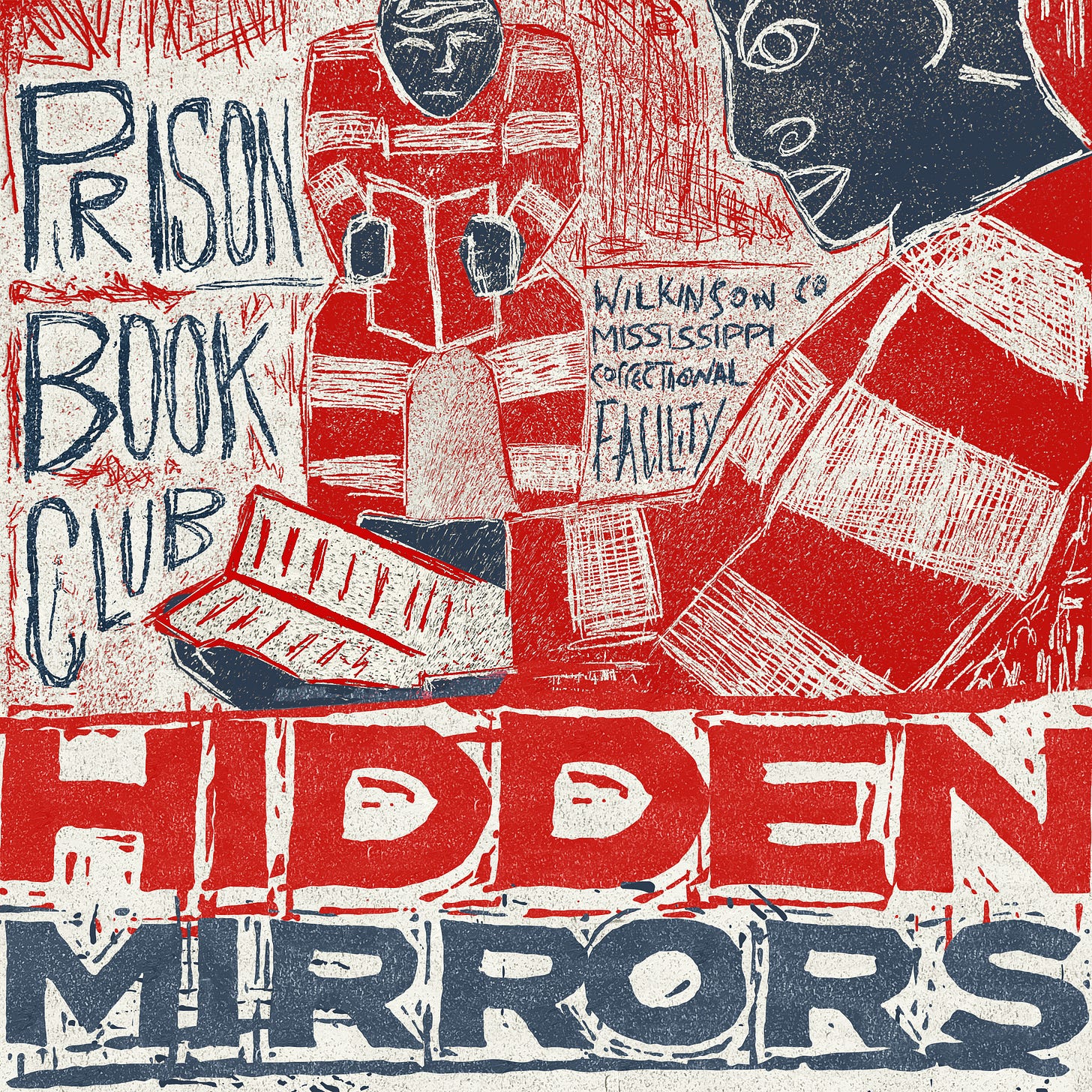

Image: “Hidden Mirrors” artwork by Houston McIntyre/Olson McIntyre

The reflections of these prisoners to their readings are so interesting. It reinforces my hope that books do effect change in people's lives. Thanks for sharing.