Opponents of Mississippi’s largest proposed solar farm await circuit court date, eye legislative remedies

Controversial “Soul City Solar” is one of two green energy projects planned for Hinds County

The familiar rebuke of industrial polluters, “not in my backyard,” has become a rallying cry for opponents of green energy projects, including the largest proposed solar farm in Mississippi, Soul City Solar, in western Hinds County.

During a June 17, 2024, public hearing on the project, opponents wore “NIMBY” t-shirts and claimed the installation would harm wildlife, mar rural vistas, contaminate surface waters and depress area property values. Many carried signs emblazoned with the words, “Say No to Big Solar.” One resident in a green NIMBY shirt approached then-Central District Public Service Commissioner Brent Bailey, pointed a finger at him and said, “You don’t live here. I do.”

Bailey, a proponent of solar power who has since left office, had earlier told the overflow crowd that nearly 40 utility-scale solar farms have been approved for construction in Mississippi and that, “These communities did not say, ‘Not in my backyard,’ they said, ‘Yes, in my backyard.’” The Public Service Commission, which regulates utilities, has approved every solar permit application that has come before it, according to current Northern District commissioner Chris Brown, though newly elected commissioners later voted to rescind solar industry incentives.

The opposition is not unique to Mississippi. The New York-based developer of one of the two solar projects planned for Hinds County, D.E. Shaw Renewable Investments, filed suit in July 2024 over a Louisiana parish board’s decision to deny a permit as a result of local opposition, which stemmed from fears of noise and wildfires and worries about aesthetics and the loss of sugarcane land. A previous lawsuit filed by property owners in Alabama prompted a Texas-based green energy company to pull out of its lease for an area wind farm.

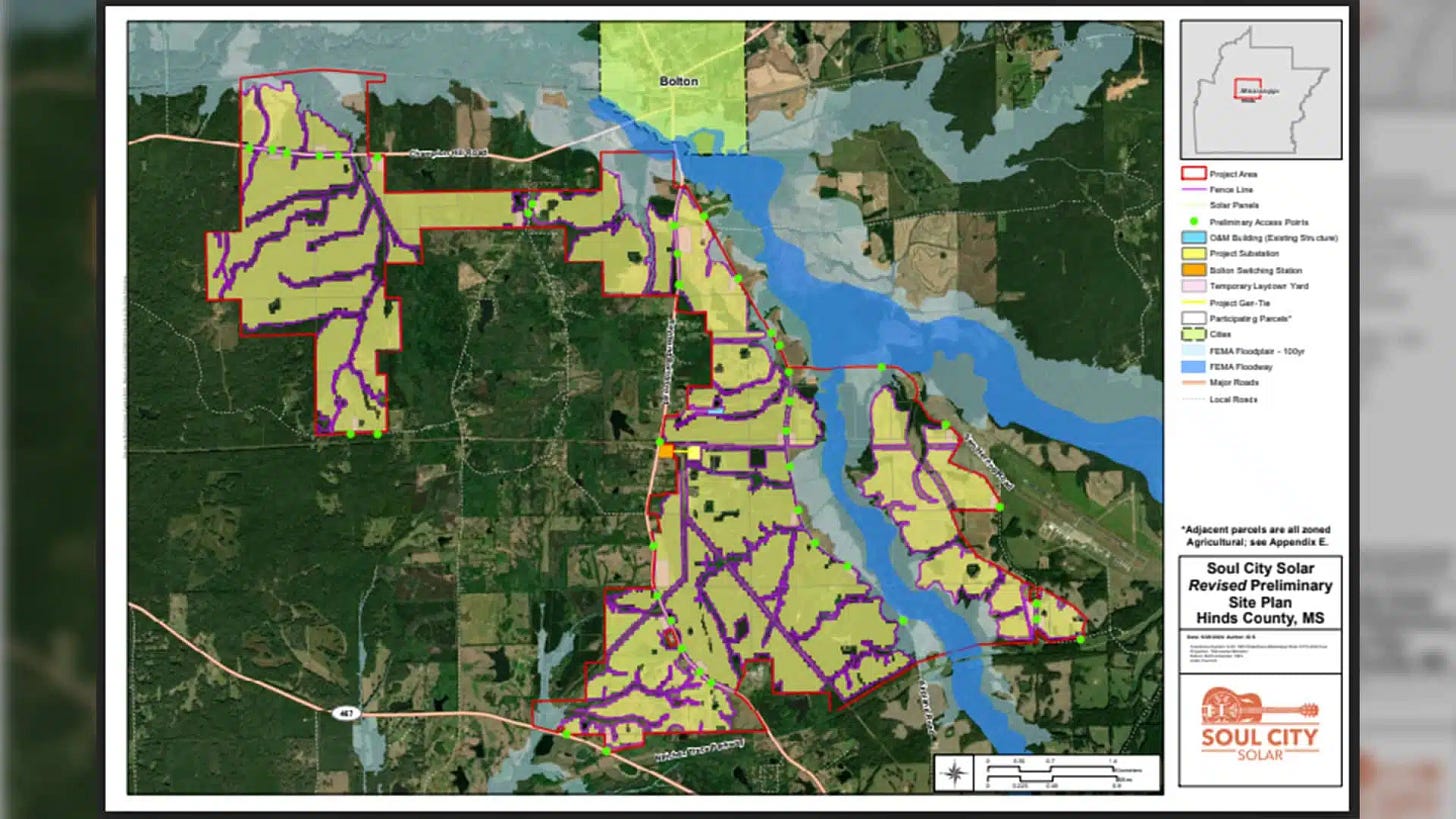

Opponents of the Soul City Solar project, planned for a rural area between the towns of Bolton and Raymond, filed suit in Hinds County circuit court, appealing a decision by the county board of supervisors to approve a conditional use permit. The supervisors had overruled a recommendation by the county zoning board to reject the plan.

“We are in the courts right now,” the leader of the Soul City opposition, Allison Lauderdale, recently told The Mississippi Independent. The case will go before Circuit Court Judge Faye Peterson in February 2025, and should Peterson uphold the supervisors’ ruling, the next stop will be the Mississippi Supreme Court, Lauderdale said.

Beyond the legal challenge, Lauderdale said that when the state legislature reconvenes in January 2025, opponents will push lawmakers to adopt state guidelines for siting solar farms, which she said are currently lacking. She declined to detail precisely what legislation would be proposed. At the June public hearing on the project, Raymond Mayor Isla Tullos urged the county supervisors to delay granting the permit for a year so more stringent guidelines could be developed.

Green energy projects are frequently targeted by political conservatives, with former president Donald Trump having falsely claimed that windmills cause cancer and that relying upon solar “would mean that America’s seniors have no air conditioning during the summer, no heat during the winter, and no electricity during peak hours.” Support for renewable energy among Republicans has dropped significantly since 2020, according to a survey from the Pew Research Center. The New York Times reported that Republican political consultant Mike Murphy, founder of a group seeking to build conservative support for electric vehicles, observed, “Solar and wind are code for Democrat. We’ve started to apply political identities to things that shouldn’t have political identities.”

Yet opposition to green energy projects often includes more liberal environmentalists. A 2023 report from the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law at Columbia University identified more than a dozen solar projects that encountered opposition from local conservation groups and environmentalists, and NPR reported that many of those projects were ultimately delayed, canceled or reduced in size.

“We’re not against green solar, but go put it on useless land, not in our backyard,” Lauderdale, who lives in Raymond, said during the June hearing, adding, “It’s going to completely destroy the ecosystem, the wildlife, our way of living, [and] it’s going to devalue our property.” The project would encompass approximately 6,000 acres currently devoted to farmland and forests.

Lauderdale, who set up a GoFundMe to raise money for fighting the project in court, told The Mississippi Independent that opposition to the project “is not political at all. It shouldn’t be. It’s all about the environment.” She claimed Mississippi has become a focus of companies seeking to build solar projects because the state has few regulations governing their siting.

“The toxicity of one solar panel is minimal, but two million panels – that’s a lot of toxicity going into our land and surrounding rivers,” Lauderdale said.

Toxic chemicals can be released when the panels are damaged, such as by hailstorms, and the glare from acres of glass can be disruptive for wildlife, Lauderdale noted. Extensive concrete foundations mean “you can never farm this land again – it’ll be useless for anything,” she added.

Though solar farms are meant to help address catastrophic climate change, the projects do sometimes have downsides, including transforming bucolic rural landscapes into sweeping industrial zones, emitting constant hums, generating localized heat, damaging native vegetation and wildlife, and leaving behind heavy metal residues. Proponents argue that the technology is proven but that certain concessions must be made, including land use changes. The two Hinds County projects, Soul City Solar and Hinds Solar, will cover a total of about 8,000 acres in the vicinity of Bolton and Raymond, west of Jackson.

Opponents of Soul City turned out in large numbers for the hearing before the board of supervisors, spilling onto the courthouse lawn. Local Facebook group pages were also filled with posts against the project, some of which cited erroneous information. Though the Hinds County planning and zoning board recommended against permitting the project and the crowd at the hearing was overwhelmingly against it, the board of supervisors approved the conditional use permit in a vote of 3-2. Supervisors representing the area all voted for it.

Lauderdale said her group’s GoFundMe has raised approximately $12,000 for legal fees and has garnered about 3,000 signatures on a petition opposing the project. The Hinds Solar project has not faced the same level of opposition, she said, “because they flew it under the radar.”

Simultaneous to the Hinds County solar farm plans, construction is underway for a $10 billion Amazon Web Services data center facility in nearby Canton. The CEO of Entergy, the area’s electric power utility, has said the company is building solar farms of its own in three Mississippi counties, including Hinds, to power the Amazon facility, in keeping with its emphasis on sustainability and use of renewable sources. Amazon, which describes itself as the largest corporate buyer of renewable energy in the United States, announced plans for another solar farm in Scott County, Mississippi. Though the Amazon facility is not directly linked to the solar farms near Raymond and Bolton, one of the installations will have a service agreement with Entergy, which, somewhat confusingly, owns a smaller, operational solar farm in the city of Jackson that is also known as Hinds Solar.

Solar farms are proliferating across the U.S. as the federal government seeks to reduce dependence on carbon-spewing fossil fuels for generating electricity. The government offers substantial incentives to encourage producers to shift to renewable sources, including an $11 billion grant and loan program announced by the Biden administration in May 2023.

The overriding question is where to build such facilities. Opponents argue that they should be situated in industrial or commercial zones, or along high powerline rights-of-way that are already compromised, rather than on productive, often scenic farmlands and near rural communities and homes. The solar sites in the Bolton and Raymond area fit the latter category but also represent large holdings in the hands of a few owners who are amenable to granting lucrative long-term leases.

The two projects are to the north and the south of Bolton (full disclosure: The northernmost Hinds Solar project is within a mile of my own home). Hinds Solar will encompass 2,300 acres straddling Jimmy Williams Road; the Soul City solar farm will spread along both sides of the Bolton-Raymond Road. Among other solar farms planned in the capital area is the 1,200-acre Ragsdale Solar Park, near Canton, to be built by EDP Renewables to feed into the Entergy grid.

The Hinds County installations will transform the affected areas into an almost unbroken sea of solar panels alongside transfer stations and battery storage facilities. Construction will require massive land clearing and grading, result in heavy truck traffic and create few permanent jobs. The backers of the Hinds Solar project estimate it will create just two full-time jobs; Soul City’s backers project 10. Hinds Solar’s projected life span is 20 years; Soul City’s is 30 years.

Both properties are in historic areas, encompassing sites of Civil War skirmishes and Native American camps. The Hinds Solar property is notably scenic, with mature trees draped in Spanish moss evoking the area’s original landscape. Yet massive land use changes are hardly new. The area’s rolling farm fields were once undisturbed native forests, and farming and timber production are themselves environmentally degrading, as is residential development that is taking place in the area.

Private property owners face few constraints on how they can utilize their land, and the potential windfalls from leasing property for solar farms is significant. Though most agreements are confidential, EDP Renewables lists $15 million in payments to local landowners for the Canton solar farm.

The speed with which the two Hinds County projects were approved alarmed some area residents. In asking the Hinds County supervisors to reject Soul City’s project until it could be further studied, Tullos, Raymond’s mayor, said, “Your no vote would be for the purpose of setting a one-year moratorium. During this one-year period, you will be leading our state in developing best practice guidance for solar development.” Tullos and others argued that the projects should be more carefully evaluated to ensure that negative impacts are minimal. From the opponents’ perspective, it appeared the projects were being fast-tracked, though one of them has been in the planning stages since 2017.

Concerns that the public was kept in the dark are not entirely unwarranted. After signs went up along roads north of Bolton announcing land use changes under consideration for the Hinds Solar project (though it was not identified by name), I phoned the posted number, which turned out to be for the Hinds County planning and zoning board. When I asked the status of the project and how to get more information about it, the spokesperson said, “That application has been withdrawn. That’s all the information I have.” Which was untrue: A week later, a neighboring landowner received a mailed notification that the application was in process, and soon after, the county approved the granting of a conditional use permit.

The Mississippi Public Service commission later briefly discussed what was described as a possible action on the Hinds Solar project, then referred the matter to commissioner Bailey to schedule a public hearing, which was held in December 2023.

Supporters of solar farms point out that the U.S. must develop clean energy sources to address climate change and that the projects require large tracts of land that are adjacent to necessary electric transmission infrastructure. Environmental and public health regulations and agreements with local governments and landowners who lease property will ensure that the projects are safe, they maintain.

According to records filed with the Mississippi Secretary of State’s Office, several corporate entities in multiple states are involved in the Hinds Solar project. Hinds Solar LLC is a Delaware corporation whose petition went before the county planning commission in September 2023. According to the secretary of state’s records, the company was formed in July 2017 with its principal office in New York City. Its managing entity is listed as DESRI Hinds Solar Development, L.L.C. (aka D.E. Shaw Renewable Investments) at the same New York address. Hinds Solar’s annual reports from 2018 to 2024 were filed by attorneys or officers in California, Missouri, New York and Texas.

Hinds Solar filed a Mississippi Public Service Commission permit application in March 2023 that listed the company as a subsidiary of D.E. Shaw Renewable Investments. At the time, the proposal was for a 150-megawatt solar site with a battery storage site on 1,200 acres of leased land, with the electricity to be sold to Entergy. The project’s scale soon nearly doubled to 2,300 acres. According to documents filed with the PSC, the company is “a leading renewable energy company that develops, owns, and operates utility-scale solar, wind, and battery storage projects throughout the United States” and is an affiliate of “a global investment and technology development firm with approximately $60 billion in investment capital.” In other words, the project is backed by venture capitalists. According to the same documents, Hinds Solar will connect directly into the Entergy Mississippi grid to provide electricity “in Hinds County and beyond.”

The parent company of Soul City has said it plans to sell the electricity through the MISO power grid, which manages energy transmission through a regional marketplace. Documents filed by Soul City Energy LLC with the secretary of state indicate Soul City’s owner is Apex Clean Energy, with a principal address in Charlottesville, Virginia. Among its officers are representatives of Apex Clean Energy Finance LLC and Apex Clean Energy Holdings LLC, which are involved in renewable energy and carbon capture projects across the U.S. Soul City Energy was formed in 2021 as Ridgeland Solar LLC but changed its name in 2023.

Given the number of entities involved, and the evolving corporate relationships, opponents suggest that the deals currently being made relative to the projects could be subject to further corporate changes – that the possibility exists the completed projects would be sold to companies that are currently unknown. This would not be unusual, as such companies frequently offload assets. Proponents say the same parameters currently being put into place would still apply.

Both Soul City and Hinds Solar will require further approval from the PSC, the Mississippi Department of Environmental Quality, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and likely from other local, state and federal agencies.

Hinds Solar has said the company expects to begin construction of its Bolton-area facility in December 2024. Apex plans to start construction of Soul City in 2025, with operations starting two years later.

As for the nationwide proliferation of such projects, the future is uncertain. The New York Times reported (paywalled) that the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act, which is “driving the transformation of America’s energy landscape,” faces an uncertain future as the presidential election looms. Trump has suggested that if he returns to the White House he would gut the law, “which is expected to pour as much as $1.2 trillion over the next decade into technologies to fight climate change such as wind turbines, solar panels, nuclear reactors, carbon capture and E.V.s, as well as the factories to supply them,” the newspaper reported.

“By contrast,” the Times reported, “Vice President Kamala Harris, who cast the law’s tiebreaking vote in the Senate, hopes to accelerate the growth of clean energy to slash greenhouse gas emissions, though that would require speeding up federal permits while overcoming local opposition and electric grid constraints.”

Images: Unidentified solar farm installation; proposed perimeter of Soul City solar farm (both via Soul City website)