Odd pairing: The U.S. Grant presidential library and progressivism in Mississippi

When the Ulysses S. Grant Presidential Library officially opened at Mississippi State University in 2017, the irony of the former president’s records being relocated from his home state of Illinois was lost on no one. As the new MSU library’s executive director said at the time, history scholars “can’t believe Grant is in Mississippi.”

Grant, the famed former Union army general and the nation’s 18th president, was once widely reviled in Mississippi for having wreaked havoc across the state during the Civil War, torching homes and public buildings, looting private property and destroying railroads and other infrastructure from Holly Springs to Vicksburg and Meridian.

Numerous scandals during Grant’s presidential administration did not help his reputation. In 1876, as Grant’s second presidential term was coming to a close, Starkville, Mississippi’s Livestock and Farm Journal noted that there was widespread Grant-loathing in the state, even among his own party, saying “not a single Republican was found who did not condemn the course of Grant in most unqualified terms.” That loathing was felt primarily among white residents who had enjoyed the benefits of the status quo that Grant had helped destroy.

In reporting on the new $10 million Grant library at MSU (also located in Starkville), the Associated Press noted that the pairing of a progressive president with a state known for its lingering obsession with the Lost Cause was viewed by some as counterintuitive.

In Mississippi, the AP reported, “Echoes of the 1861-1865 war still linger in debates over whether Confederate flags, war monuments and holidays are tools of white supremacy or markers of Southern heritage.” At the time, Mississippi residents and elected officials were “locked in a never-ending debate over redesigning its state flag,” which featured the Confederate battle emblem in its canton corner.

Yet, according to the article, supporters of the library’s new home saw it as less ironic than intentional – as an effort to cross the divide.

“It was our view that going to the South with these collections would somehow, somehow, help people to understand each other and survive as a family,” Frank Williams, a former Rhode Island Supreme Court chief justice and president of the Ulysses S. Grant Association, which owns the collection, said.

Grant earned his reputation as a brilliant military strategist during the Civil War’s Vicksburg campaign, when he undertook a dangerous, previously untried approach, cutting off his army from its lines of supply and pilfering resources from the local population. His brutal tactics devastated Mississippi and led to the fall of Vicksburg, which reopened the Mississippi River to commerce and divided the Confederacy in two, dooming the cause of southern secession.

During a 47-day Union siege of Vicksburg, the Rebel flag had flown prominently atop the county courthouse, making it a coveted Union prize. After the city fell to Grant’s forces on July 4, 1863, the banner was quickly lowered and replaced by the United States flag. A subsequent axiomatic phrase for taking bold, decisive action was “like Grant took Vicksburg.”

“The fate of the Confederacy was sealed when Vicksburg fell,” Grant wrote in his memoirs. “Much hard fighting was to be done afterwards and many precious lives were to be sacrificed; but the morale was with the supporters of the Union ever after.”

The word “after” carries a lot of weight here, evoking both the war’s remaining battles and the long crucible of Reconstruction, a period of painful reentry of former Confederate states into the Union, during which the federal government ensured, at least for a time, suffrage for former enslaved men and other free men of color.

By 1885, Grant had been relaunched and more or less rebranded, and was more likely to be viewed, even within Mississippi’s conservative power structure, as a respected former adversary, as this academic paper noted. The change of heart was in large measure prompted by his having gone soft on efforts to contain the power of reactionary southerners during Reconstruction, which enabled an effective backlash against African American voters. During his reelection campaign, Grant returned to Vicksburg, and this time a parade was held in his honor. In a speech to city residents, he said that in 1863 he had come in through the back door, and he was happy that the city now held open the front door for him.

Though Grant was generally regarded as a progressive president, his record in that regard was uneven. He signed into law the 1871 Ku Klux Klan Act, which gave him the power to use military force to fight white supremacists, and the 1875 Civil Rights Act, the Fifteenth Amendment, granting the right to vote to Black males. But in 1875, when asked to enforce the KKK act in Mississippi, Grant was mindful of having lost support in Congress and, afraid of losing more, turned a blind eye toward the paralegal organization’s infamous abuses. During his presidency, Mississippi’s former ruling class reclaimed political power through corruption, intimidation and violence, resulting in the removal of nearly all the more than 200 Black elected officials. It was at the end of this period that the state adopted its pro-Confederacy flag, and it would take decades of more bloodshed before the state’s past wrongs began to be righted.

Supporters of MSU’s new Grant library have tended to portray it as something of a progressive lodestar, a means of enabling reconciliation and more open historical dialogue. Michael Ballard, an MSU professor and coordinator of what is known as the Congressional Collection, noted that the repository’s relocation was “further proof of the enlightenment of a state that progresses continually despite its detractors.” It is true that Mississippi has made significant strides, and today has more African American elected officials than any other state. Yet, characterizing the state as a suitable venue for progressive debate was (and remains) something of a hard sell: “Enlightened” is not the first word that comes to mind in the context of its historical or contemporary political dynamics.

There are meanwhile lingering questions about how, exactly, the decision was made to move the collection from Southern Illinois University-Carbondale, in Grant’s home state, and how MSU was selected as the new repository. The move took place with comparatively little fanfare, and state Sen. Hob Bryan observed during a recent interview with The Mississippi Independent that it had still not received the attention it deserved.

In fact, the library did not technically “move” to MSU in 2017, as it had not previously existed as a presidential library – it was simply a collection housed in Illinois that was moved to Mississippi, starting in 2008. The official library designation was made internally in 2012 and formally announced in 2017.

The collection contains 15,000 linear feet of correspondence, research notes, artifacts, photographs, scrapbooks and memorabilia from Grant’s birth in 1822 through his military career, Civil War triumphs, presidency and post-White House years. It also includes some odd artifacts, including a lock of Frederick Douglass’s hair.

There has been debate about the relocation and its underlying motivations. A legal dispute was the initial catalyst. The relocation decision stemmed from a fraught (and largely hidden) institutional dynamic: a hush-hush Me, Too episode in Illinois that prompted behind-the-scenes academic jockeying for position.

John Y. Simon, a now-deceased professor at Southern Illinois University, had spent five decades amassing, transcribing and annotating the collection of what is known as The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant. Simon, a widely recognized expert on Grant, was later accused of verbally harassing three women employed by the Ulysses S. Grant Association and the Southern Illinois library. In 2008, the university came under fire for allegedly not following due process by shunning and locking Simon out of his office before an investigation was begun into the sexual harassment claims. At that point, the unhappy Grant association began searching for a new home for the collection. A reconciliation that would have permitted Simon to return to teaching at Southern Illinois was reportedly being negotiated at the time of his death.

According to Ryan Semmes, a professor at MSU and current director of research at the Grant library, credit for the selection of Mississippi for the new repository goes to John Marszalek, a renowned Civil War historian and MSU distinguished professor emeritus. After Simon passed away, the same year the Grant association withdrew the collection from Southern Illinois, Marszalek was named his successor as executive director and managing editor of the Grant papers. At that point, Marszalek took the initiative – basically, like Grant took Vicksburg.

“He made the case that if you move the collection here, not only would the editors be able to continue to publish The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant, but then we would make the collection available to researchers in a public way, in terms of letting historians come in and use the material, and then also having an exhibit space and trained personnel that could work on the collection,” Semmes told The Mississippi Independent. Though Semmes did not come out and say it, Simon had been a bit stingy with sharing the research, according to David Carlson, the dean of library affairs at Southern Illinois.

In 2008, the collection was considered a de facto though not an officially recognized presidential library. The National Archives runs modern presidential libraries, “but your 19th century and 18th century presidents, they are kind of on their own,” Semmes said. “They’re usually attached to a boyhood home or to an association, which, we are home to the Grant association.” The library was initially housed in the cramped basement of the Mitchell Memorial Library on the MSU campus in Starkville and in 2012 designated itself Grant’s official presidential repository.

After five years of renovations, which included a move to the campus library’s top floor, the facility now houses gallery spaces, a reading room, offices, preservation and processing rooms, climate-controlled storage, and an auditorium. Administrators are in the early stages of designing a new, freestanding structure for the library at the edge of campus on Highway 12, Semmes said. Among the goals is to increase public accessibility by providing more non-student parking and room for school buses, campers and shuttles. Semmes said the facility will be more than a museum and research center for scholars, and will serve as a center for other types of civic engagement.

In Semmes’ view, Mississippi is an ideal location for examining Grant’s life and legacy. “If you’re going to study Grant’s presidency, you’re studying Reconstruction,” he said. “And you can’t study Reconstruction without studying Mississippi’s history as well.”

Mississippi’s history encompasses its share of wild contradictions, of both progression and regression, including but not limited to the Reconstruction era. Grant, Semmes noted, was himself “a man full of contradictions that kind of reflect America at that time. And so, I think with our museum space, we hope to tell, not only his story, but the story of America through the lens of Ulysses S. Grant in the 19th century.”

Marszalek told the AP that the library’s collection dispels several lingering myths about Grant, such as that he was a drunkard, a butcher of a general who won only due to superior troop numbers, or a failure as president. The museum doesn’t shy away from less-flattering episodes, including Grant’s attempts to shield subordinates in his administration from prosecution during tax and bribery scandals. But overall, “He was the general who won the great victory that preserved the Union and rid the nation of the curse of slavery,” Marszalek said. “He is also considered now by historians to be the first modern president.”

Media coverage of the library’s official opening naturally noted that it coincided with debate over Mississippi’s divisive state flag. In 2001, a referendum had been held over whether to change the flag, in which voters overwhelming opted to keep it. In 2015 and 2016, more than 20 flag-related bills, some calling for another statewide referendum, were introduced in the legislature, but none made it out of committee. Then, in 2020, as part of the nation’s racial reckoning over the murder of George Floyd, the legislature again put the issue before voters, who this time passed a referendum to change the flag.

At the time of the library’s opening, MSU, like other state universities, had already opted to cease flying the contentious flag. As a result of the vote, the state flag now flying at MSU includes a more inclusive emblem, a magnolia blossom. The enemy flag that Grant and his troops once encountered on the battlefield has been consigned to museums and the occasional nose-thumbing bumper sticker.

It would have been a strange pairing indeed had a representation of the Confederate flag flown over the institution housing the Grant presidential library, given his role in defeating the rebellion.

Removal of the former state flag from the MSU campus, a year before the relocation of the Grant library, paired with the later adoption of a more inclusive flag, were seen as progressive moves, but “progress” is a relative term. Like several of his predecessors, Mississippi Gov. Tate Reeves has continued to declare a “Confederate Heritage Month,” most recently in April 2024.

The Grant library is actually one of two presidential libraries in the state, the other being one that represents its historical antithesis: the official library of Jefferson Davis, the sole president of the failed Confederate States of America, which is located on the grounds of his last home, Beauvoir, in Biloxi.

The Davis library’s website notes that he wrote his two-volume tome The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government while living at Beauvoir after the Civil War, and that he “archived greatness as the symbol of the South. The pages of history reveal no other instance in which a vanquished people so idolized the leader of a cause that failed.”

After Davis moved to New York City, Beauvoir was for decades used as a home for “more than 2,000 veterans, wives, widows, and servants,” according to the home’s site. Artifacts and papers housed on the ground floor of the adjacent presidential library were destroyed during Hurricane Katrina in 2005. A replacement building, housing the artifacts and records that survived on the second floor, was dedicated in 2013.

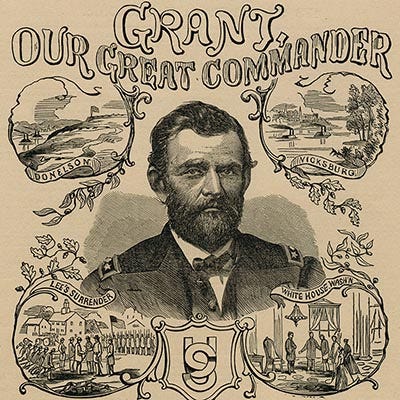

Images: Grant cartoon, via Ulysses S. Grant Presidential Library; Gov. Tate Reeves speaking to the Sons of Confederate Veterans in Vicksburg, via the Mississippi Free Press (via R.E. Lee Camp SCV Facebook group)

Kerry Rose Graning is a Mississippi writer, artist and lapsed archaeologist. Her work has appeared in the Oxford American, the Bitter Southerner, and Hakai, among other publications. She is currently at work on a documentary about the SEC, a family road trip, and the scattering of her grandfather’s ashes.

What a great article. Thank you for sharing this information.