In Mississippi Delta, even conservative farmer feels betrayed by tariffs

Growers face dire consequences as a result of Trump's trade war

Editor’s note: This is the first in a series that looks at how tariffs and cuts to federal programs are exacerbating economic challenges for Mississippi farmers. Black farmers have long dealt with a system that disadvantages them, and farmers in general have faced problems related to inflation and market uncertainty. Even established farmers – including politically conservative ones – are now experiencing the downsides of a government many see as running counter to their best interests.

On an average day, Ray Crawford is awake long before the sun rises in the Delta. His house is quiet, aside from the hiss of the coffeemaker and the low murmur of the morning news, which Crawford listens to for hints of what will become of his livelihood.

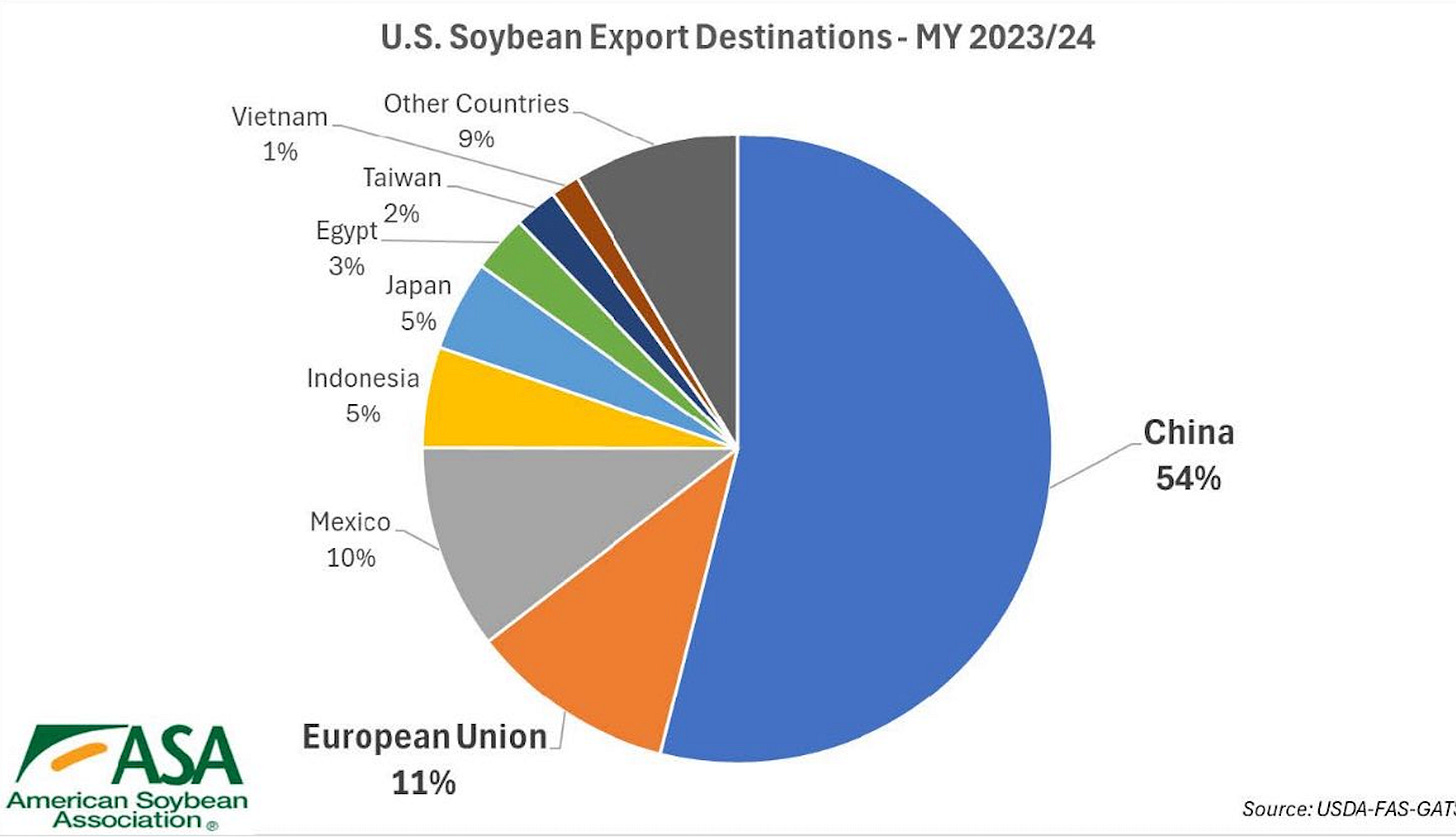

Lately, it’s almost always bad news, largely due to President Donald Trump’s ongoing trade wars. Crawford grows soybeans, and as of Sept. 1, 2025, not a single U.S. soybean from the upcoming harvest has been sold to China, which was previously the largest buyer of the U.S.-grown product.

As a result, Crawford, like most soybean farmers nationwide, finds himself on the edge of financial survival. Independent farmers are accustomed to enduring the occasional bad year, but the latest trade war with China feels different, Crawford said.

Crawford is among legions of Mississippi farmers feeling the dramatic impacts of what many see as an unnecessary undermining of their global markets. Though soybeans are front and center, other growers are also under threat, U.S. House Rep. Bennie Thompson told The Mississippi Independent.

“They are all terrified of losing their livelihoods,” Thompson, whose district includes the Delta, said of farmers caught up in the ongoing tariff crisis. “I hear from the corn growers. I hear from the beet people. I hear from the rice people. If they can’t sell to China, Canada or Mexico, they are in real trouble. These countries have other options, and we’re chasing them away.”

For decades, China --the world’s biggest buyer of soybeans -- reliably pre-purchased more than half of America’s crop, sending billions of export dollars into small farming communities like those in the Mississippi Delta. That lifeline began to weaken in 2018, when Trump’s tariffs on Chinese steel prompted Beijing to retaliate with a 25 percent duty on soybeans. Trump has reignited the trade war during his second term.

Crawford, who considers himself politically conservative and has been farming in the Delta for four decades, told The Mississippi Independent, “I’m not sure if I’ll survive this one.” He also grows long-grain rice on his Quitman County farm, but soybeans are the mainstay. Recently, he said, “I cleaned out my daughter’s horse trailer in case I have to sell it. I’m bare bones, and I bet a lot of us are thinking the same thing.”

For Crawford, an average day begins at around 4 a.m. Soon, his pickup is rumbling across 4,400 acres of rich Delta soil that since 1983 has sustained him and his family, despite occasional shortfalls resulting from low crop prices, bad weather and other agricultural vagaries. As a result of the financial crisis related to the tariffs and cuts to federal farm programs, “This could be the end,” he said.

“It used to be you’d have a bad year or two, but now every year is a shortfall,” Crawford said. “Every dime I spend puts me further in the red. I’m going backwards and I don’t have any other ways to explain it.” He said he is disappointed by what’s going on in Washington, D.C. and within the Trump administration. “There have got to be better ways to make a deal,” he said. “You don’t kill mosquitoes with sledgehammers.”

As China builds new ties with Brazil to fulfill its soybean needs, a significant hole has opened in Mississippi’s revenue stream, leaving state farmers wondering what to do with their harvests. The worry is that the current trade war will ruin current crop prospects and ultimately result in permanent trade deals between China and other large importers with exporters including Brazil, eliminating U.S. farmers’ largest markets.

The math of farming—bushels per acre multiplied by prices per bushel, minus seed, fertilizer, debt service, employee costs and the rest—no longer works. A bushel of soybeans currently fetches about $10 – close to the same amount the crop sold for in 1977, and far below the $12 or $13 needed to cover costs.

Costs associated with soybean farming have meanwhile soared during the last four years, according to an analysis released by Mississippi Lt. Gov. Delbert Hosemann. “Up 124 percent for soybeans,” he wrote in a February 2025 statement, adding that the increased costs resulted in an average loss of $161.40 per acre of soybeans. “Our farmers are in trouble, and the ripple effects are being felt across the entire state.”

Even before Trump began his second trade war with China, Mississippi farmers, who produce more than $7 billion annually and account for 18.6 percent of the state’s economy, faced a grim reality, according to Hosemann’s stats. At the root of the crisis is a punishing mix of inflation, surging input costs and depressed crop prices, magnified by fierce international competition. Farmers face skyrocketing expenses for essentials such as seed, fertilizer and fuel, leaving many operations running at a loss. What was once an occasional hardship has hardened into a years-long struggle, made worse by banks growing increasingly hesitant to extend credit to farmers to enable them to keep planting – and now, by the tariffs and the loss of their main customer.

Statewide agricultural losses are estimated at $550 million, a shortfall felt across Mississippi’s economy, totaling $3.5 billion in lost spending, Hosemann noted. Soybeans account for about $1.6 billion of Mississippi’s economy, according to 2023 estimates by Mississippi State University.

In some ways, the struggles of American farmers is an old story. Delta farmers long grappled with seasonal floods that have been reduced by federal investments in levees and other flood control projects. The Dust Bowl of the 1930s forced many cash-strapped farm families westward, reshaping the nation and inspiring Roosevelt’s New Deal. The 1980s farm crisis hollowed out rural America, as high interest rates, collapsing land values and falling crop prices drove families into bankruptcy. Many never returned to their fields.

Increasingly, large corporations, including multinationals, have bought up and consolidated what were formerly family farms squeezed from every direction—competition from corporate agribusiness, globalization, financial crises, and now inflation. The loss of family farms has been particularly acute for Black landowners.

For today’s soybean farmers, the math of survival has largely been calculated in Washington, D.C. and Beijing.

China was the bedrock of America’s soybean market for two decades, reliably pre-purchasing more than half of U.S. exports to feed its massive livestock industry. Then came 2018’s trade war. Overnight, farm exports collapsed and China’s share of U.S. soybeans fell to 18 percent, gutting farm income and prompting Congress to send $28 billion in emergency aid. Although sales rebounded during the Biden years—by 55 percent in 2023 and 50 percent in 2024—the U.S.-China relationship has never fully recovered.

Instead, China has poured money into Brazil, building highways, railroads and ports to carry Brazilian soybeans to the Pacific Ocean. Brazil is now the world’s top soybean producer, and by 2025, is projected to outpace the U.S. by 42 percent. The global soybean market has shifted south, leaving American farmers to wonder if their largest customer will ever return. The tariffs, farmers like Crawford contend, will exacerbate this trend.

The American Soybean Association estimates farmers lost $9.4 billion annually during the first trade war, and has warned that those losses alone would take decades to undo – even before the current trade war.

“There’s just not any margin for error in the current farm economy,” said Caleb Ragland, president of the American Soybean Association, who is himself a farmer in Kentucky. “Instead of beating each other up with higher and higher tariffs—it’s like punching each other in the face—we need solutions.”

The Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy blasted Trump’s trade policies as “erratic” and “chaotic,” saying they neither acknowledge the problem nor offer any solutions. Mississippi, where soybeans are one of the top agricultural exports, is particularly vulnerable. Nearly every bushel grown in the state once had a chance of being shipped to China. Now farmers must sell to processors or smaller markets, often at a loss.

Crawford said he basically gave away an entire soybean harvest in 2018 because he couldn’t sell it. “What are we going to do with all the soybeans?” he asked.

When soybeans go unsold, farmers face a series of costly and risky choices: Store them in grain bins and pay steep fees while hoping prices recover; sell them at a loss to domestic processors for oil or feed; scramble to reach smaller and less reliable export markets; or depend on government aid. Each path carries risk. Bins can lead to spoilage while storage debt mounts, and global prices may never rebound, meaning every unsold bushel becomes both a financial burden and a gamble.

Seemingly counterintuitively, a May poll found that 70 percent of 400 U.S. producers surveyed believed the tariffs would ultimately strengthen the farming industry. Crawford doesn’t share that view. Though the tariffs are front and center, he points to other political failures. The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s disaster relief program, which was supposed to ease financial pain from recent crop disasters, ended up significantly slashing payments by cancelling one program and replacing it with another that disadvantaged small farms, he said.

Mississippi’s U.S. Sen. Cindy Hyde-Smith celebrated those cuts as a win for farmers. When launching her reelection campaign, Hyde-Smith framed herself as a champion of Mississippi farmers and touted her close relationship with Trump. At her kickoff event at the Mississippi Agriculture and Forestry Museum in Jackson, she was flanked by U.S. Agriculture Secretary Brooke Rollins, who praised her as “a warrior’s warrior” for agriculture. Hyde-Smith stressed her willingness to fight federal agencies—even clashing with the U.S. Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. over pesticide restrictions—and cast herself as a trusted Trump ally. “I can send a text to President Trump, and he responds,” she told the crowd.

Yet at another public meeting in Ridgeland, Mississippi, Hyde-Smith said past trade policies were unfair and that she was “pretty excited about benefits that will come from the tariffs.” In June, she acknowledged the obvious to Successful Farming magazine. “The T word, the tariffs have been brutal,” she said. “No one said this was not going to be painful, but I really think we’re trying to get to a place on the other side that we will benefit from this. But I’ll tell you, it’s a rough road right now, I’ll be honest with you.”

Mississippi Agriculture and Commerce Commissioner Andy Gipson applauded Trump’s reciprocal tariffs back in April, saying that they “will set the stage for the renegotiation of better trade deals that will benefit American farmers.”

Neither Hyde-Smith nor Gipson responded to questions from The Mississippi Independent.

Crawford said he no longer believes the promises that politicians make. “They promise the moon and pay us moon pies,” he said.

The impacts include delays in purchases like equipment upgrades and forgoing personal expenditures like vacations, Crawford noted. “The last time I took one, I was in the hospital for open-heart surgery. That’s what stress does, and that’s about as close to a vacation as I’ll get.”

Every morning, Crawford still wakes before dawn, checks his irrigation systems and coordinates with his crew. Yet anxiety over the future is always close at hand. “Some friends can go home and sleep fine,” he said. “I’m not wired like that. I’m up at night trying to figure out how to get out of this mess.”

What’s at stake is not just his farm but a way of life. Without farmers, rural communities wither, and their schools, stores and churches starve for reinvestment. “You lose more than just seeing the fields planted,” Crawford said. “You lose communities.” That is particularly true in the Delta, much of which has no economic mainstays other than agriculture.

In a potentially beneficial turn of events for farmers, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit in late August ruled that Trump went too far when he declared national emergencies to justify imposing sweeping import taxes on almost every country in the world, though the ruling stopped short of striking down the tariffs immediately, allowing the administration time to appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court.

The ruling was seen as a major setback for Trump, whose erratic trade policies have decimated farmers, rocked financial markets, paralyzed businesses with uncertainty and raised fears of higher prices and slower economic growth. The question for farmers is whether the damages are irreversible – whether countries like China will cement trade deals with Brazil and other nations that it can more dependably rely upon.

Like most farmers, Crawford has weathered floods, droughts, booms and busts over the years. Also like most farmers, he is part of a conservative political base. Yet for him the current crisis seems unnecessary and careless. As a result of what he sees as a fabricated trade war, it all comes down to a simple unfortunate fact: With China gone, America is left with too much supply and too little demand.

“We’re sitting on a mountain of soybeans we don’t know what the hell to do with,” Crawford said. He has considered retiring early, renting out his land and sparing his family and workers the ongoing financial and emotional toll of relying upon a failing modern farm. Yet loyalty keeps him tethered. “I care about those people,” Crawford said of the families who depend on his farm. “I don’t want to just walk out on them.”

Image: Crop harvest on Crawford Farms (courtesy Ray Crawford)