From Reconstruction promise to Trump downsizing: The precarious history of public education in Mississippi

When Mississippi established its first public school system in 1868, it represented one of Reconstruction’s most revolutionary achievements. The new state constitution, drafted by a biracial convention that included 16 Black delegates, mandated free public education for all children between five and 21 years old. It was a radical departure in a state where teaching enslaved people to read had been a crime just three years earlier.

Now, as the Trump administration announces plans to “return education to the states,” Mississippi finds itself at a crossroads that echoes a fraught educational history. The state that pioneered public schooling during Reconstruction, then systematically dismantled it under Jim Crow, and later resisted its integration for decades, now faces renewed questions about its commitment to public education—notably through the mechanism of “school choice” vouchers that could redirect public funds to private schools.

Reconstruction: Education in the hands of the state

The architects of Mississippi’s public education system understood that they were building something unprecedented. As author Jere Nash documents in his recent book Reconstruction in Mississippi, 1862-1877, the state’s 1868 constitution did not just permit public schools—it required them, establishing a state superintendent and county school boards to ensure implementation. This wasn’t abstract idealism. It was essentially practical nation-building by formerly enslaved people and their allies who recognized education as essential to citizenship and economic participation. Notably, the constitution did not stipulate that public schools be segregated.

The system faced immediate challenges. White landowners resisted taxation for schools that would educate Black children. Resources were scarce in a war-devastated economy. Yet by 1875, Mississippi had established more than 3,000 schools serving more than 150,000 students—roughly split between Black and white children, though in rigidly segregated facilities.

The 1890 constitutional convention, designed explicitly to disenfranchise Black Mississippians, gutted public education funding. Delegates eliminated the mandate for universal education and structured financing to starve Black schools while maintaining white ones. What followed was a century-long period of separate and deliberately unequal education—a system that invested lavishly in white students while relegating Black children to overcrowded, underfunded schools with shortened terms and hand-me-down materials.

This wasn’t just neglect—it was policy. State leaders openly defended the arrangement as necessary to white supremacy. The gap widened through the first half of the 20th century, even as Mississippi remained one of the poorest states in the nation. By the 1950s, Mississippi spent less per pupil than any other state, with Black schools receiving a fraction of what white schools did.

Resistance, integration and the modern system

The landmark Supreme Court ruling in Brown v. Board of Education in 1954 was meant to be transformative, but the State of Mississippi mounted massive resistance for more than a decade. The legislature passed laws to prevent integration, abolished compulsory attendance requirements and created tuition grant programs explicitly designed to fund white students attending segregated private academies. The tuition grant program, established in the 1960s, represented an early iteration of “school choice”—one rooted transparently in racial avoidance rather than educational improvement.

When federal courts finally forced integration in 1970 under Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education, white flight accelerated dramatically. During the 1969-1970 school year, institutions emerged like Madison-Ridgeland Academy and multiple schools operated by the segregationist Citizens Council as havens for families fleeing integrated public schools. These “seg academies” proliferated across the state, particularly in the Delta and in counties with large Black populations. The exodus drained not only students but community investment, parental involvement and tax support from public schools serving increasingly Black and poor student populations.

The post-integration era did, however, bring some progress. Federal oversight through desegregation orders pushed Mississippi toward equalizing funding among districts. The Education Reform Act of 1982 established the first comprehensive accountability system, creating standards and assessment requirements that began addressing decades of educational neglect. By the 1990s, Mississippi was making measurable gains in reading scores and graduation rates, slowly building the equitable public education system that Reconstruction had promised but never delivered.

The funding crisis

Progress has since been systematically undermined by the state’s chronic failure to fund its own education formula. Since the Mississippi Adequate Education Program (MAEP) was established in 1997 to ensure adequate funding for all districts, the legislature has fully funded it only twice—in 2003 and 2007. The cumulative shortfall exceeds $3 billion.

The consequences are concrete. Mississippi spends $12,394 per pupil annually, ranking 45th nationally in school spending. By comparison, neighboring Tennessee spends $12,400 per pupil; Alabama, $13,461; and Louisiana, $13,200. The national average is $16,990 per pupil. Mississippi teachers earn an average salary of $53,704—dead last among all states and roughly $13,000 below the national average. Starting teachers make $41,500, while those with advanced degrees and decades of experience top out at around $71,400.

Even this chronic underfunding isn’t distributed equally. Rural districts, which disproportionately serve Black and low-income students, face the steepest challenges. Districts have been forced to increase class sizes, eliminate arts and music programs, defer building maintenance, and forego technology upgrades. The same structural inequities that characterized Jim Crow segregation persist through geography and property wealth rather than explicit racial classification. The effects remain strikingly similar.

In this historical context, what might “returning public education to the states” look like?

The “school choice” debate

Mississippi is currently debating the expansion of its education voucher system. The state operates a limited Education Scholarship Account (ESA) program, established in 2015, that serves only students with disabilities. Funded at $3 million annually with a maximum award of $7,829 per student, the program serves approximately 400 students, with another 150-plus on a waiting list. Gov. Tate Reeves has called for expanding funding to clear the waitlist.

Legislative leaders are eyeing much broader expansion. State Rep. Jansen Owen, a Republican from Poplarville and the House’s leading school choice advocate, has expressed interest in creating a universal or near-universal ESA program. House Bill 1433, introduced during the 2025 legislative session, would have created ESAs for students in “D” and “F” rated school districts, funded with their portion of per-pupil state aid. The bill died in committee, but supporters view it as a template for future efforts.

Proponents argue that ESAs would expand opportunity, particularly for families whose children attend struggling public schools or have needs that aren’t being met. They frame school choice as empowering parents and introducing competitive pressure that could improve public schools. Organizations such as Empower Mississippi and the Mississippi Center for Public Policy contend that Mississippi’s existing ESA program demonstrates demand and point to the waitlist as evidence that families want alternatives.

Critics counter that universal vouchers would devastate public schools that are already starved of resources. They note that Mississippi’s private schools serve only 11 percent of students statewide (about 55,000 students compared to 440,000 in public schools), with 58 percent of those private schools concentrated in just 10 counties—primarily the Jackson metro area and the Gulf Coast. Most of Mississippi’s 82 counties have five or fewer private schools, and many rural counties have none. Private schools in Mississippi are 80 percent white in a state with a population that is 38 percent Black; can reject students with disabilities or behavioral issues; face minimal accountability for academic performance; and are not required to accept voucher amounts as full payment.

The research on voucher outcomes provides limited support for either side’s claims. Studies from Louisiana, Indiana, Ohio and Washington, D.C. have documented significant academic declines for students using vouchers, particularly in math, with negative effects persisting for multiple years. Research published in education policy journals such as the Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis found students in Louisiana’s voucher program experienced test score drops equivalent to the learning loss from COVID-19. A 2022 Brookings Institution analysis examining four rigorous studies concluded that “on average, students that use vouchers to attend private schools do less well on tests than similar students that do not attend private schools.”

Some research suggests positive effects on high school graduation rates and college enrollment, though these studies examine older, smaller programs targeting specifically low-income students. The academic debate reflects genuinely mixed evidence, with program design, targeting and regulatory structure appearing to matter significantly for outcomes.

Trump’s vision and Mississippi’s reality

The Trump administration’s promise to “return education to the states” combines federal withdrawal with encouragement for universal school choice programs. For Mississippi, this represents compounding pressures: reduced federal support for schools that depend heavily on it, combined with state policies that could redirect remaining funds away from public education.

Mississippi receives 23.3 percent of its education funding from federal sources—the highest percentage in the nation and well above the 11.1 percent national average. This reflects the state’s poverty levels and the concentration of students qualifying for Title I support. Federal funds provide roughly $2,800 per pupil in Mississippi. Any reduction in federal education spending would hit Mississippi harder than wealthier states.

If Mississippi simultaneously implements universal vouchers while federal support declines, public schools serving 89 percent of the state’s children would be squeezed in a fiscal vise. Arizona’s experience offers a cautionary preview: The state’s universal voucher program, projected to cost $65 million in its second year, actually cost more than $708 million, with 75 percent of recipients already enrolled in private schools simply claiming new subsidies. The fiscal pressure contributed to Arizona’s $1.4 billion budget shortfall, forcing cuts to infrastructure and other services.

The legislative landscape ahead

The 2026 legislative session will likely see renewed voucher proposals, though passage remains uncertain. Mississippi’s Republican legislative leadership is divided, with rural representatives—whose districts lack private school options—skeptical of programs that would drain resources from their public schools. Urban and suburban Republicans from the Jackson metro are, DeSoto County and the Gulf Coast are more supportive, reflecting their constituents’ greater access to private alternatives.

Beyond ESAs, debates are expected over the following:

Tax credit scholarship programs. These would allow corporations to redirect tax liability to private school scholarships rather than paying taxes to the state. Such programs, operating in states such as Florida and Arizona, function as vouchers while avoiding direct state appropriations, potentially appealing to legislators wary of explicit voucher votes.

Expanded open enrollment. Less controversial proposals would allow students to transfer between public school districts more easily. The state House has already passed versions of this legislation, though implementation details remain contentious.

Charter school expansion. Mississippi authorized charter schools in 2013 but limited them to Jackson and districts rated C, D or F. Proposals to expand charter authorization statewide resurface regularly.

Curriculum restrictions. Separate from funding debates, coming proposals include those targeting what can be taught regarding race, gender and United States history—part of broader national trends in Republican-controlled legislatures.

The fundamental tension concerns funding. Mississippi has not fully funded MAEP in 18 years, creating cumulative deficits exceeding $3 billion. Whether the state adds voucher programs while that gap persists, increases overall education funding to accommodate multiple systems, or continues current spending levels while shifting allocations will shape Mississippi education for generations.

Interest groups have staked clear positions. The Mississippi Association of Educators and the nonpartisan education advocacy organization The Parents’ Campaign, oppose voucher expansion, arguing public funds should strengthen public schools. Empower Mississippi and the Mississippi Center for Public Policy, both conservative policy organizations, advocate aggressively for universal school choice. Business groups remain divided, with some chambers of commerce supporting vouchers as workforce development tools while others worry about weakening the public schools that educate most future workers.

An unfinished promise

Mississippi’s public education system was established during Reconstruction with the promise of universal access. That system evolved through periods of deliberate inequality, resistance to integration, gradual progress toward equity, and chronic underfunding. The current debate over school choice represents another chapter in this history.

The outcomes will depend on multiple factors: program design, funding levels, accountability requirements, and whether expansion occurs alongside increased overall education investment or as a reallocation of existing resources. Research from other states provides some guidance, but Mississippi’s unique history, demographics, rural character and existing educational challenges mean the state’s experience will be its own.

As federal policy shifts toward state control and state legislators weigh their options, Mississippi faces fundamental questions: What does the state owe its children in terms of educational opportunity? How should public resources be distributed? What role should the state play in ensuring educational access and quality? And how does Mississippi’s history of educational promises made and broken inform current choices?

The answers will emerge through legislative debate, policy implementation, and ultimately, through the educational experiences of Mississippi’s 495,000 school-age children—whether they attend public schools, private schools or navigate between systems. What remains certain is that education policy decisions made in the coming years will reverberate for decades, shaping not just individual student outcomes but Mississippi’s economic prospects, civic culture and commitment to the public good.

The Reconstruction delegates who wrote education into Mississippi’s constitution understood that universal public education was essential to building a democratic society. Their vision was systematically dismantled, partially rebuilt, and has never been fully realized. Whether Mississippi finally fulfills that 157-year-old promise or pursues a fundamentally different vision of education as a private good funded by public subsidy will be determined by choices made in the months ahead—choices that will define what kind of state Mississippi aspires to become.

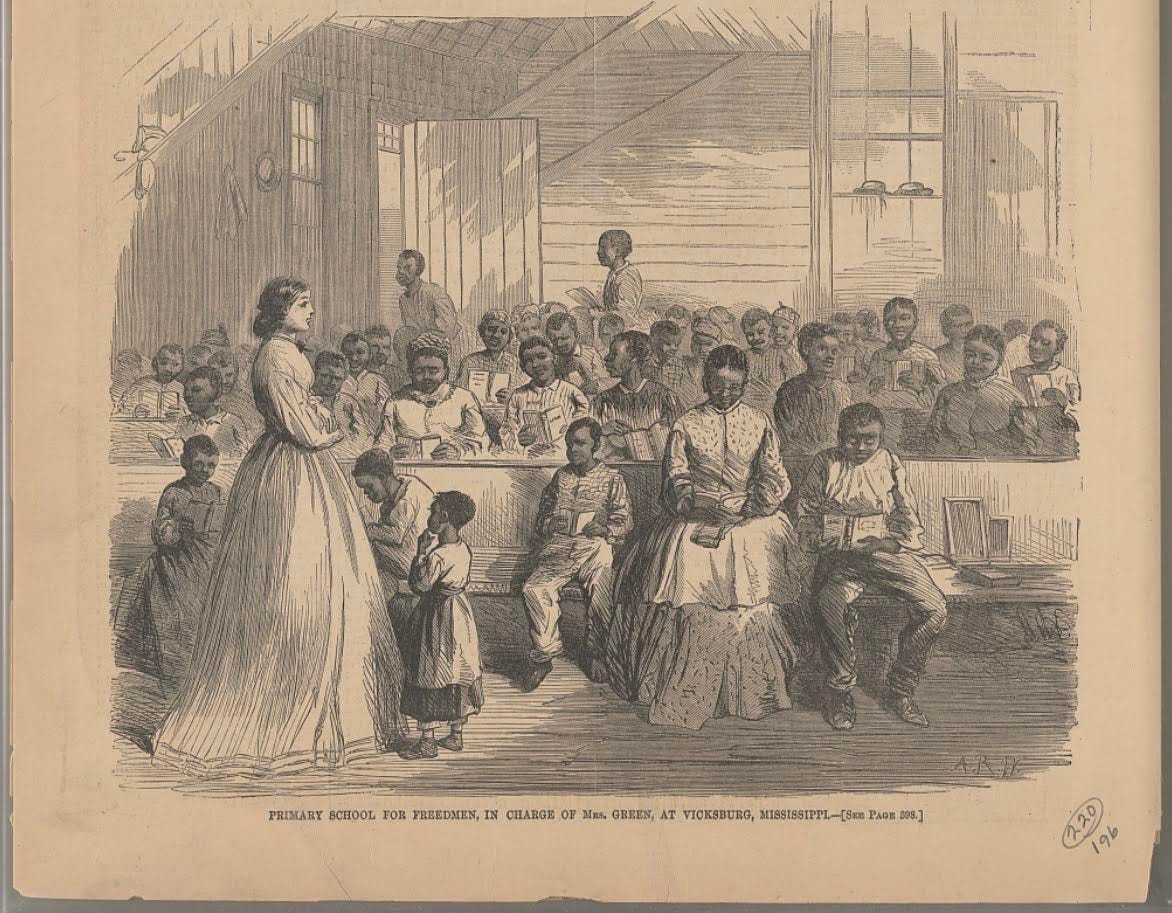

Image: Freedmen’s school, Vicksburg (via Library of Congress)

I cannot start to address all the facets of your article, Pro and Con, but I want states to be in control of its children's education. Leave the Federal government out of dictating what is to be taught. Mississippi can do a lot better in being self supporting of its education system by raising property taxes on land, not residences. Much of the land that gives Mississippi its character is under taxed in my opinion.