A half-century ago, state Rep. Robert Clark Jr. argued that 'school choice' was unconstitutional, yet lawmakers are once again pushing it

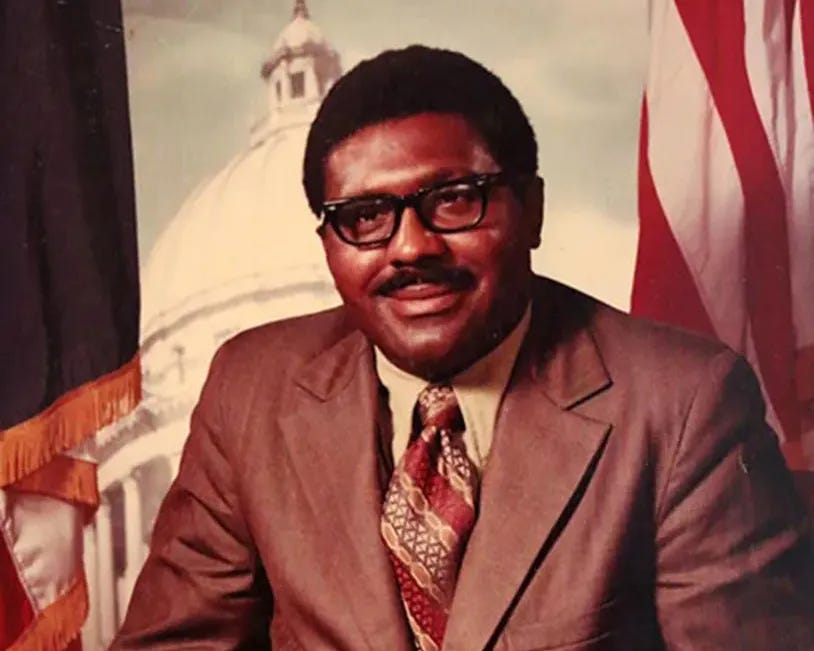

In 1970, Robert Clark Jr., the first Black legislator in Mississippi since Reconstruction, cast the only vote against a “freedom of choice” education plan that aimed to maintain segregation through state-supported private schools.

In taking his solitary stance, Clark highlighted the risks involved in diverting funds from what were then newly integrated public schools to support segregation academies.

More than 50 years later, language and aims similar to those that Clark opposed have resurfaced in a new legislative push to create tax-credit programs modeled after federal school choice policies, which would likewise divert funds from public to private schools. Opponents say the current effort raises questions about equity and constitutional responsibilities, which is what Clark argued back in 1970.

Before the trailblazing Clark broke barriers as Mississippi’s first Black legislator since Reconstruction, in 1968, he had spent two decades in classrooms. From 1953 to 1973, he taught in secondary and postsecondary schools across the state, cultivating a reputation as a principled educator before turning fulltime to politics.

After becoming a lawmaker, Clark, who died on March 4, 2025, at his home in Ebenezer at age 96, often spoke of his ambition to lead the House Education Committee—a goal he realized in 1977, when House Speaker C.B. “Buddie” Newman appointed him to the post after the previous chair, George Rogers, left to join President Jimmy Carter’s administration.

Clark’s early years in the legislature were marked not by influence, however, but by isolation. He frequently stood as the lone dissenting vote on major legislation -- a solitary figure challenging the prevailing political order. That isolation reached a defining moment in January 1970, as Mississippi entered the realm of federally mandated school desegregation.

In his statewide address that month, Gov. John Bell Williams acknowledged the end of segregated schools but urged parents to embrace “freedom of choice” between public and private schools. His somber words reflected a region still resisting change. The governor framed the proposal as empowering parents, but critics warned it masked efforts to preserve segregation through state-supported private academies.

The “freedom of choice” plan was a state-sanctioned policy designed to desegregate schools by giving parents the option to select their child’s school. However, this approach effectively served to uphold segregation. It enabled the creation of new private “segregation academies” by providing targeted tax incentives and relied upon Black parents’ hesitation to enter predominantly white schools. A federal district court struck down the program in Coffey v. State Educational Finance Commission, ruling that it violated the Fourteenth Amendment by enabling parents to avoid integrated schools. The court also noted that the practice conflicted with Mississippi’s own constitution, which forbids public funds from flowing to non-public schools.

Gov. Williams’s proposed new legislation declared that “no student shall be assigned or compelled to attend any school on account of race, color, creed or national origin, or for the purpose of achieving [racial] equality in attendance.”

Clark was blunt in his rebuttal. Williams’s plan, he argued, would “only weaken the already poor educational system we have in Mississippi” by funneling public dollars into private institutions. On March 20, when the House overwhelmingly endorsed the governor’s proposal for freedom of choice, Clark cast the lone vote against the bill. “How long are we in Mississippi going to keep on ignoring the mandates of the Constitution?” he asked, warning that the bill would only deepen public unrest.

The close of Mississippi’s 1970 legislative session marked a decisive setback for Gov. Williams’s push to advance the series of “school choice” initiatives designed to ease the financial burden on white families turning to private academies to avoid federally mandated school integration.

One Senate-backed bill would have reduced state income taxes by $6 million, with targeted relief for middle- and lower-income families struggling to cover private school tuition. Another measure, approved early in the session by the House, offered a tax credit of up to $500 for contributions to educational programs at accredited Mississippi schools. A third proposal sought to extend local school tax benefits to parents who withdrew their children from public schools in favor of private institutions.

Despite multiple proposals circulating through the House and Senate, lawmakers ultimately allowed the measures to stall amid political gridlock.

The centerpiece “freedom of choice” legislation collapsed in the session’s final hours. The Senate balked at a House amendment that would have exempted local school boards from compliance with federal desegregation orders—language that directly challenged the courts’ authority.

With its refusal to adopt the measure, Mississippi became the first Deep South state to break ranks with a broader regional effort to codify resistance to integration under the banner of school choice.

Clark’s continuing battle against freedom of choice

In the early months of 1970, Clark stood at the forefront of this escalating battle over public education and civil rights. Frustrated by the state’s sluggish response to the Brown v. Board of Education ruling, he was vocal in his criticism of both local and national leadership.

That January, President Richard Nixon’s domestic advisers floated the idea of forming a “blue ribbon southern group” to address school desegregation. Although Nixon publicly supported the Brown decision—calling it both constitutionally and morally correct—he was careful not to interfere with ongoing court cases. His administration drew a strategic line: Address only de jure segregation, dismiss de facto concerns. The Nixon administration expressed a critical distinction between the two forms of racial segregation: de jure segregation, which was mandated by law, and de facto segregation, which typically occurred as a result of residential patterns and socio-economic factors. This difference helped determine how deeply the federal government would be involved in schools.

“Call it de facto and drop it,” Nixon instructed his officials, aiming to avoid broader federal enforcement of integration policies.

While Nixon’s statements gave some Black leaders reason for cautious optimism, they did little to sway Clark. He continued to push for grassroots solutions to empower the Black community.

On Jan. 11, 1970, Clark convened a coalition of civil rights and education leaders at the Mississippi Teachers Association office in Jackson. Representing organizations including the NAACP, the National Education Association, and the Freedom Democratic Party, the group laid the groundwork for what came to be known as the Educational Resources Center. The initiative aimed to ensure Black Mississippians could engage in a unitary school system with “dignity and integrity,” contributing meaningfully to community education.

Still, the legislative battles raged on. In early February, two measures aimed at bolstering private schools passed through the Mississippi House. One reduced licensing costs for private school buses; the other allowed individuals aged 16 and older to take out loans for private education. Clark condemned the bills as unconstitutional, calling them indirect tax subsidies that favored segregationist academies. He predicted they would not survive judicial scrutiny.

The tension escalated further when Gov. Williams vetoed $5 million in funding for four Head Start programs, affecting roughly 4,000 children. Clark wrote directly to President Nixon, denouncing the move as racially charged and harmful to efforts aimed at voluntary school integration. The veto, he argued, deepened distrust and discouraged white participation in the programs.

In a rare federal intervention, the U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare responded to Clark’s appeal. On March 21, 1970, Secretary Robert Finch overrode the governor’s decision, approving more than $2 million in grants to sustain the Head Start programs. The move highlighted the federal government’s growing role in supporting early childhood education in underserved communities.

As court-ordered integration took effect across the South, Mississippi saw a sharp rise in the establishment of private schools, often today described as segregation academies. Many white families fled public schools, seeking what they framed as “quality” education. Clark remained a fierce critic of this exodus and the state’s continued financial support for private institutions, calling instead for full investment in public education.

Mississippi’s effort to funnel public money into private education collided head-on with federal courts and the state constitution. Now, more than 50 years later, lawmakers are once again testing those boundaries.

As federal courts forced the desegregation of Mississippi’s public schools, legislators created a tuition grant program that allowed families to use state money to pay for private education. The grants—initially capped at about $180 per student and later increased—helped fuel the growth of all-white segregation academies that sprang up across the state.

The debate resurfaces

Fast-forward to 2025, and the fight over public money for private education has resurfaced. Lawmakers are weighing school choice bills—including a proposal to let students in low-performing districts take state dollars to private schools—while the Mississippi Supreme Court considers whether the state can direct millions of federal relief dollars to private campuses.

Supporters argue that families deserve more options, particularly in communities where public schools struggle. Opponents say the proposals repeat a painful history of diverting resources from underfunded public schools and risk running afoul of the same constitutional prohibitions that doomed the 1970 plan.

As the issue of school choice has returned to the forefront under the banner of “education freedom,” President Donald Trump, who has repeatedly called school choice “the civil rights issue of our time,” secured a provision in his signature legislative platform, the “One Big Beautiful Bill Act,” creating the nation’s first federal school choice program.

The program, built on tax credit scholarships, allows taxpayers to donate up to $1,700 annually to nonprofits supporting private education, receiving a dollar-for-dollar credit in return. Unlike traditional deductions, which reduce taxable income, the program provides a full match—an unprecedented shift in education funding.

In August 2025, Mississippi’s House Select Committee on Education Freedom heard testimony from two Trump administration officials who argued that the program could transform educational opportunities in the state.

Yet echoes of 1970 remain. Some lawmakers have questioned whether school choice could erode public education or clash with constitutional provisions, just as Clark argued decades earlier. Lindsey Burke, the Trump administration’s deputy chief of staff for policy and programs, insisted the plan does not violate Mississippi’s constitution. “The funds are not directly funding a school,” she said. “They are funding the family who then chooses a school.”

In this way, Mississippi once again finds itself at the center of the debate, having embraced modern versions of school choice—charter schools, vouchers, education savings accounts and open enrollment. Supporters argue these programs empower parents and give children trapped in failing schools a way out. Critics warn that the measures echoe the old freedom of choice system, draining money from public schools and worsening racial and economic divides.

Legally, these programs are constitutional—for now. Courts have generally upheld vouchers and charters, even when public money flows to religious schools, as in the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2022 decision in Carson v. Makin. But the Mississippi Constitution also requires lawmakers to maintain a system of free public schools. If funding shifts too heavily toward private or religious institutions, the state could face lawsuits challenging whether it is meeting that obligation.

The real test may not be in the courtroom, but in classrooms across Mississippi. If “choice” results in further segregation or starves public schools of resources, it risks repeating history—reviving the very inequalities the courts once declared unconstitutional.

In a press release regarding the establishment of the select committee, Mississippi House Speaker Jason White (R-West) emphasized that “education freedom” will be the foremost priority as lawmakers prepare for the upcoming legislative session. The committee plans to meet several more times in the coming months to gather testimony from both supporters and critics. Lawmakers will use the findings to draft legislation for the 2026 session, illustrating that the debate over who controls Mississippi’s classrooms—and how they receive funding— is unresolved.

As Mississippi lawmakers debate school choice in 2025, they are revisiting ideas that first surfaced more than half a century ago under segregationist Gov. John Bell Williams. Then, as now, the central question was whether the state should use tax policy to ease the financial pressure on families seeking private education.

Williams, who complied with federal desegregation court orders, pushed for tax relief measures that would make private schooling more attainable. Today, lawmakers are advancing proposals with strikingly similar contours.

One Senate-backed bill this year would reduce state income taxes by $6 million, with a focus on middle- and lower-income families struggling to pay private school tuition. The approach mirrors Williams’s emphasis on lowering tax burdens to give parents more flexibility in where they educate their children.

Other proposals move along a parallel track. A House measure offered a $500 tax credit for contributions to accredited educational programs, reflecting a broader push for tax-credit scholarship programs and donation-based models that have become central to modern school choice campaigns.

The rhetoric in both cases shares a consistent theme: shifting financial control from the state to families.

One point of divergence lies in the treatment of local school taxes. Williams supported extending local tax benefits to parents who withdrew their children from public schools, effectively enabling families to reclaim a portion of what they had paid into local districts. Today, lawmakers have shown little appetite for restructuring local tax obligations, even as the broader the focus is squarely on state-level tax credits and vouchers. The debate now centers on parental choice and public education funding.

Derrion Arrington is an award-winning historian from Laurel, Mississippi, and a graduate of Tougaloo College. He currently works for the ACLU of Mississippi and is the author of two books: : Standing Firm in the Dixie: The Freedom Struggle in Laurel, Mississippi, and the forthcoming Robert Clark: The Rise of Black Politics in Mississippi.

Image: Robert Clark Jr. in an undated photo (courtesy Mississippi Department of Archives and History)

Great article. Appreciate your inclusion of Clark’s ideology and bravery of standing firm, and a look at how unfortunately things really haven’t changed much in Mississippi. Looking forward to your new book on Robert Clark, Jr.